Using Workplace Absences to Measure How COVID-19 Affects America’s Workers

Posted on by

Since September 2017, NIOSH has monitored the monthly prevalence of health-related workplace absences among full-time workers in the United States using nationally representative data from the Current Population Survey (CPS). This data can be a useful way to measure the effect COVID-19 has had on the U.S. working population.

What Are Health-related Workplace Absences?

Health-related workplace absences occur when a worker misses work as a result of their own illness, injury, or other medical issue. Since March 2020, this measure has also included workers quarantined because of an exposure to a person who has COVID-19.

A full-time worker is defined in the CPS as someone age 16 or older who usually works at least 35 hours a week. For a particular week each month, a sample of full-time workers are asked how many hours they actually worked. If they worked fewer than 35 hours, they are asked about the reason for their absence. These 1-week measures are meant to represent absenteeism for all weeks in the month.

Monitoring the Trends, Watching for Alerts

Health-related workplace absences, measured as the percentage of full-time workers who did not work or who worked reduced hours due to illness each month, correlate with the occurrence of influenza-like illness.[1],[2],[3],[4] Because of this correlation, monitoring these absences is a useful way to measure the impact of influenza pandemics or seasonal influenza epidemics on workers. In March 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, NIOSH researchers did not know whether this was also true for COVID-19.

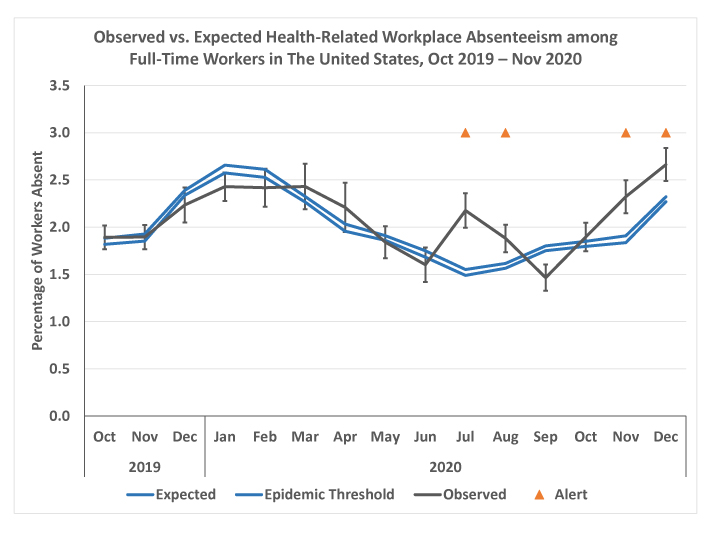

Since the pandemic began, we have continued to monitor health-related workplace absences to better understand the impact COVID-19 has had on the U.S. workforce. The results of our surveillance analyses are displayed as a series of data visualizations, or graphs. When absences are significantly higher than expected,[5] our system signals an “alert,” shown by arrows on the graphs. The graphs are updated monthly with the previous month’s data. Since the beginning of 2020, we have been monitoring absenteeism trends in relation to COVID-19 surges.

April 2020

At the peak of the initial period of rapidly increasing COVID-19 cases, many non-essential workers were furloughed, laid off, or working from home due to state-imposed restrictions on businesses and stay-at-home orders. As a result, increases in health-related workplace absences were only seen in certain essential worker groups.[6]

May–September 2020

In May, many businesses began reopening, travel began to increase, and unemployment and teleworking started to decrease. COVID-19 cases began increasing in late June. An unprecedented summertime spike in absences corresponded with the summer surge in COVID-19 cases that peaked in July and moderated in August and September.

In July, health-related workplace absences signaled an alert after increasing significantly from June. The July increase was broad-based, with alerts signaled in almost all demographic, geographic, and occupational subgroups. This suggested a more widespread impact of the pandemic on the expanding population of employed workers.

Though absences declined, they remained higher than expected in August before returning to expected baseline levels in September. This supported the idea that health-related workplace absences closely track the incidence of COVID-19.

In September, the economy continued to rebound, people continued to travel, and in-person instruction resumed in many schools.[7]

October–December 2020

Beginning in October, and sustained by the onset of colder weather and the U.S. holiday season, which led people to spend more time indoors and to have more in-person social interaction, COVID-19 cases increased dramatically throughout the remainder of the year, reaching higher levels than at any other time during the pandemic.[8]

In October, absences among full-time workers increased significantly from September but were not significantly higher than expected for that month. Despite unusually low numbers of influenza and influenza-like illnesses in November and December 2020, absences continued increasing significantly, this time signaling alerts for both months.

While absences are normally expected to increase in the fall, this year’s increase was earlier and steeper than expected. For both November and December, absences were higher than in the same month for any of the previous five years. The increasing absences coincided with the surge in COVID-19 cases that began in October and continued through the fall.

The fall 2020 surge in Covid-19 cases was also associated with a broad-based increase in health-related workplace absences. This trend supports the idea that absenteeism surveillance is useful as a measure of COVID-19’s effect on the workforce.

Workplace Absences Can be Used to Measure the Effect of COVID-19 on Workers

These findings suggest that, as with influenza-like illness, health-related workplace absences can be a useful measure of the impact of COVID-19 on the working population, especially since standard occupational elements are not systematically captured in COVID-19 surveillance data. In the absence of such data, these findings confirm the value of this approach to COVID-19 pandemic surveillance.

To learn more, visit our Absenteeism in the Workplace webpage.

How does information on health-related workplace absenteeism help inform your understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on workers? Please comment below.

Matthew R. Groenewold, PhD, is an Epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Field Studies and Engineering, Health Informatics Branch.

Hannah Free, MPH, is a Technical Information Specialist in the NIOSH Division of Field Studies and Engineering, Health Informatics Branch.

Amy Mobley, MEn, is a Health Communications Specialist in the NIOSH Division of Field Studies and Engineering, Health Informatics Branch.

References

[1] Groenewold MR, Burrer SL, Ahmed F, Uzicanin A, Luckhaupt SE. Health-Related Workplace Absenteeism Among Full-Time Workers — United States, 2017–18 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:577–582.

[2] Groenewold MR, Konicki DL, Luckhaupt SE, Gomaa A, Koonin LM. Exploring national surveillance for health-related workplace absenteeism: Lessons learned from the 2009 influenza A pandemic. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2013; 7:160-166.

[3] National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Sickness absenteeism among full-time workers in the US, August 2009. NIOSH eNews. 2009; 7:6. Accessed December 30, 2011.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics. Issues in Labor Statistics. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2010. Illness-related work absences during flu season. Accessed December 30, 2011 Occupational groups correspond to the CPS Major Occupational Group recodes, which are groupings of Census Occupation Codes.

[5] The percentage of full-time workers absent is estimated each month using CPS survey data; each estimate has a margin of error. Absences are considered significantly higher than expected when the lower limit of the estimate’s margin of error is higher than the “epidemic threshold.” The epidemic threshold is calculated using baseline absenteeism data from the previous five years, averaged by month, and information about the likely variation of these baseline data.

[6]Groenewold MR, Burrer SL, Ahmed F, Uzicanin A, Free H, Luckhaupt SE. Increases in Health-Related Workplace Absenteeism Among Workers in Essential Critical Infrastructure Occupations During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, March–April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:853–858.

[7] https://www.edweek.org/leadership/map-where-are-schools-closed/2020/07; https://returntolearntracker.net/

[8] Honein MA, Christie A, Rose DA, et al. Summary of Guidance for Public Health Strategies to Address High Levels of Community Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Related Deaths, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1860-1867.

2 comments on “Using Workplace Absences to Measure How COVID-19 Affects America’s Workers”

Comments listed below are posted by individuals not associated with CDC, unless otherwise stated. These comments do not represent the official views of CDC, and CDC does not guarantee that any information posted by individuals on this site is correct, and disclaims any liability for any loss or damage resulting from reliance on any such information. Read more about our comment policy ».

A four day work week would be less taxing on physical and emotional well being for all working Americans. But do to risk of lost of health insurance and poor pay rates will lead to sicker people at younger ages. Not speaking of a three day weekend I am speaking of weekend and one mid day week. Except for parents/guardians or health care (dialysis etc) different people off on different days. lead to more jobs and people able to get to medical appointments. It could help with social distancing in the work place too,

thanks for this post very informative