Bloodborne Pathogen Exposures Continue in Operating Room Settings

Posted on by

Despite legislation and improved technology, data from Massachusetts hospitals show that sharps injuries have increased in the operating room (OR) [1]. These injuries place healthcare workers at risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens (BBPs). There is an urgent need to renew efforts to protect healthcare workers inside the operating room.

The Massachusetts data highlight a gap and the need to establish a national surveillance program that would help hospitals develop further measures to prevent sharps injuries.

The surgical environment is unique among healthcare settings.

The OR is a high-risk setting for sharps injuries and bloodborne pathogen exposure. Healthcare workers in the OR can be exposed to large amounts of blood. Working in the OR requires extensive use of sharp instruments, which can often be difficult to see because of the focus on the surgical site. Multiple members of a surgical team must work together in a small space. These circumstances place surgical personnel at higher risk of sharps injury and blood exposure than most other healthcare professionals.

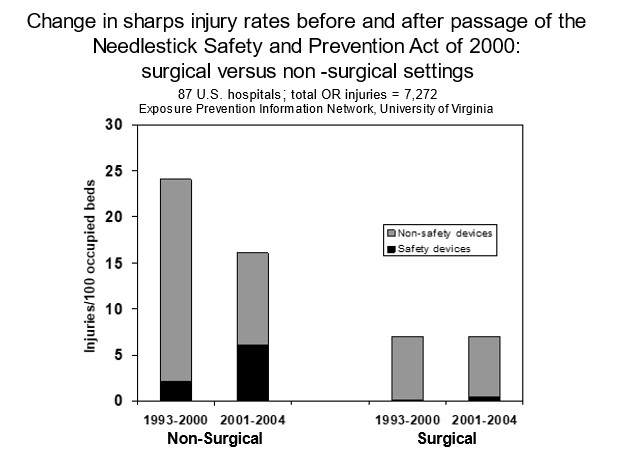

Despite legislation changes in 2000 and advances in sharps safety technology, several studies have found surgical sharps injuries failed to decrease during a time when nonsurgical sharps injuries decreased significantly (see Figure 1) [2–5].

Figure 1: Despite legislation changes in 2000 and advances in sharps safety technology, surgical injuries failed to decrease during a time when nonsurgical injuries decreased significantly.

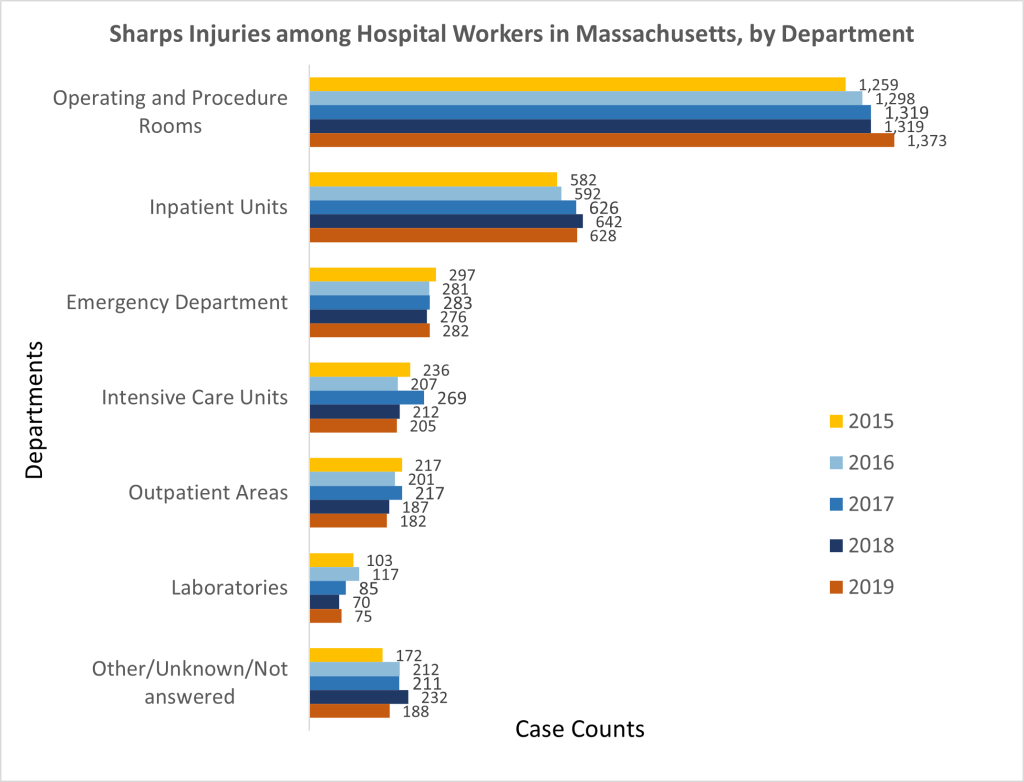

There is no national surveillance system to assess whether exposures have improved in the OR and to describe the root causes of sharps injury in the OR setting. However, data from the Massachusetts Sharps Injury Surveillance System from 2002 to 2020 show that sharps injuries in 89 hospitals in the system were consistently highest in the operating and procedure rooms [1]. It is likely that hospitals in other states are experiencing the same situation.

Figure 2. Sharps injuries among hospital workers in Massachusetts by department from 2015-2019.

Why BBPs exposures are a concern for healthcare workers.

Bloodborne pathogen exposures are a concern for healthcare systems and hospitals because:

- Vaccines cannot prevent all BBP infections. No vaccine is available to prevent hepatitis C or HIV infection. The hepatitis B vaccine is preventive; however, some healthcare workers are unvaccinated or do not respond to the hepatitis B vaccine. Titer testing is recommended to confirm response to HBV vaccine.

- Effective post-exposure prophylaxis is not available for all BBPs (e.g., hepatitis C).

- There is no national surveillance of BBPs by occupation. This could guide and monitor efforts to prevent these exposures among hospital healthcare workers.

- All healthcare providers who perform invasive procedures with sharp instruments are at risk for injury. The OR setting presents the greatest risk.

Information to prevent BBP exposures is spread across many federal agencies and institutions. This includes the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and other parts of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Joint Commission, state health departments, private businesses, and others.

There are ways to prevent exposure to BBPs in the Operating Room.

NIOSH, other CDC Centers, OSHA, and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) have resources to prevent bloodborne pathogens among all healthcare workers. These apply to all healthcare workers, including operating room (OR) personnel [6–7].

NIOSH recommends ways for healthcare workers to protect themselves and their patients when providing medical services. These steps are based on the hierarchy of controls which are ordered based on their general effectiveness, from most effective to least effective:

- Elimination or substitution

- Work practices and administrative controls

- Engineering controls

- Personal protective equipment (PPE)

Employers should provide sharps-free equipment, work practices, engineering controls (including safety-engineered sharps), and PPE to prevent exposure to blood and other body fluids. OR staff and other workers should closely adhere to previous requirements and participate in safety product selection to reduce sharps injuries among healthcare workers.

Specific examples of key prevention measures are listed below.

1. Blunt Suture Needles

Suture needle injuries pose the greatest risk of sharps injury to the surgeon and scrub technicians. The effectiveness of the use of blunt-tip suture needles in reducing sharps injuries is supported by several randomized studies and case series that demonstrate a decrease in the rate of glove puncture from 38% down to 6% —and down to zero in some cases—following the adoption of blunt-tip suture needles when it is clinically appropriate [8-12].

2. Double Glove

Glove failure represents a significant risk of BBP exposure for perioperative personnel. The ACS recommends the universal adoption of the double glove (or under glove) technique to reduce exposure to body fluids resulting from glove tears and sharps injuries [9,12].

3. The Neutral Zone or Hands-Free Technique

The hands-free technique requires the surgical team to designate a sharps-neutral zone to pick up and release surgical sharps, such as needle holders, scalpels, and syringes with needles. Examples of sharps-neutral zones are a towel, Mayo stand, or magnetic pad. With this technique, the scrub technicians and surgeon do not directly hand instruments back and forth.

A partial hands-free technique may be used whereby sharps are directly handed from the scrub technician to the surgeon but then returned to the scrub technician via a neutral zone. [9,12]

4. Work Practices

The ACS supports work practices designed to eliminate, protect, or standardize the use of sharp instruments in the OR. The ACS also recommends using structured evaluations and user-based criteria that include performance standards, task analysis, simulation, and training programs for devices intended to reduce sharps injuries in the OR [8-12].

What else can be done to keep workers safe?

Sharp injuries are preventable. Despite the advances in minimally invasive surgery and a laparoscopic approach in surgery, the operating room is still a high-risk setting for occupational sharps injuries and bloodborne pathogen exposures.

Even with legislation, changes in work practices, and improvements in engineering controls, workers are still being exposed to BBPs, particularly in the OR. This supports the need to renew efforts to protect these healthcare workers. What should we be doing to further prevent these exposures and minimize sharps injuries?

We invite surgeons, other healthcare workers, and employers to share their sharps prevention success stories, challenges, and ideas to improve this issue among healthcare workers.

Ahmed Gomaa, MD, ScD, MSPH, is a Medical Officer in the NIOSH Division of Field Studies and Engineering.

Sarah Hughes, MPH, is a Lieutenant in the US Public Health Service and a Research Health Scientist in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Sue Afanuh, MA, is a Technical Information Specialist in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Amy Mobley, MEn, is a Health Communications Specialist in NIOSH’s Health Informatics Branch in the Division of Field Studies and Engineering.

References

- gov [2023]. Needlesticks & sharps injuries among Massachusetts hospital workers. Annual reports. https://www.mass.gov/lists/needlesticks-sharps-injuries-among-massachusetts-hospital-workers

- Jagger J, Berguer R, Phillips EK, Parker G, Gomaa AE [2010]. Increase in sharps injuries in surgical settings versus nonsurgical settings after passage of national needlestick legislation. J Am College Surgeons 210(4):496–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.018

- Jagger J, Berguer R, Phillips EK, Parker G, Gomaa AE [2011]. Increase in sharps injuries in surgical settings versus nonsurgical settings after passage of national needlestick legislation. AORN J 93(3):322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2011.01.001

- Makary MA, Al-Attar A, Holzmueller CG, Sexton JB, Syin D, Gilson MM, Sulkowski MS, Pronovost PJ [2007]. Needlestick injuries among surgeons in training [2007]. N Engl J Med 356(26):2693–26999. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17596603/

- gov [2022]. Data Brief: Sharps injuries among hospital workers in Massachusetts: findings from the Massachusetts Sharps Injury Surveillance System, 2020. download (mass.gov)

- CDC [2011]. The national surveillance system for healthcare workers (NaSH). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/NaSH/NaSHReport-6-2011.pdf

- OSHA [2001]. Bloodborne pathogen standard. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 29 CFR 1910.1030. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1030

- OSHA [2023]. Bloodborne pathogens and needlestick prevention. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. https://www.osha.gov/bloodborne-pathogens

- ACS [2016]. Revised statement on sharps safety. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, October 1.https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/international-safety-center-releases-consensus-sharps-safety/

- NIOSH [2007]. Use of blunt-tip suture needles to decrease percutaneous injuries to surgical personnel. Safety and Health Information Bulletin SHIB 03-23-2007 ∙ DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2008-101 (supersedes 2007-132) https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2008-101/

- FDA, NIOSH, OSHA Joint Safety Communication. Reduce needlestick injuries and the risk of subsequent bloodborne pathogen transmission to surgical personnel. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21956

- AORN [2019]. (AORN) 3 New Ways to Improve Sharps Safety. Denver, CO: Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. https://www.aorn.org/article/2019-10-22-Improve-Sharps-Safety

Posted on by