Critical Steps Your Workplace Can Take Today to Prevent Suicide

Posted on by

Employers can play a vital role in suicide prevention. Historically, suicide, mental health, and well-being have been underrepresented in workplace health and safety efforts, but this is changing. In some European countries, there are workplace standards for workplace psychosocial hazards that put workers at risk for suicide. Additionally, in France, employers have been made accountable for toxic workplaces and management practices that contributed to worker suicides.[1] Some of the latest workplace research and best practices for the prevention of suicide are summarized below as a resource for employers and workers.

The Workplace as a Risk Factor for Suicide

The effects of work on suicide are complex. Work can be protective against suicide as a source of personal satisfaction and meaning, interpersonal contacts, and financial security. However, when work is poorly organized or when workplace risks are not managed, work can raise suicide risk in some workers.

Workplace Suicide Risk Factors

There are many different factors that have been shown to adversely affect mental health, and directly or indirectly impact suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and death. Many of these workplace factors interact with non-workplace factors to further increase suicide risk.

Workplace factors that can contribute to an increased risk of suicide include:

- Low job security, low pay, and job stress [2] [3] 4] [5]

- Access to lethal means [6] [7]–the ability to obtain things like medications and firearms

- Work organization factors such as long work hours, shift work [8] [9]

- Workplace bullying [10]

In addition, some occupations have been found to have higher suicide rates than others.

Workers in occupations with a higher risk of suicide may include:

The Workplace as an Education, Prevention, and Intervention Site

Workplaces are an important setting for suicide prevention efforts. Workers spend a significant amount of time at work and co-workers and supervisors often notice important changes in thoughts or behaviors that may be signals for increased suicide risk. Additionally, most people who die by suicide are of working age (16-64).[11] Many workplaces are engaged with improving worker mental health and well-being but are still reticent to consider and include suicide prevention in their programming. Since many workplaces already have structures and resources in place to help employees access various types of assistance—adding suicide prevention is a logical next step.

However, suicide prevention in the workplace is not one size fits all. What works and what is needed for one occupation or industry may not be applicable to another. Some general strategies that positively impact workplaces include:

- limiting access to lethal means,

- providing peer support,

- increasing access to mental health services, and

- reducing stigma to encourage easier access to quality care.

Recent Resources

U.S. Surgeon General

In 2022, the U.S. Surgeon General released a Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-being. The Framework provides a roadmap that workplaces can use to support mental health and well-being centering strategies around five essential components:

- Protection from harm,

- Work-life harmony,

- Mattering at work,

- Connection & community, and

- Opportunity for growth.

This landmark document also includes examples of programs and intervention efforts from a range of businesses and industries, demonstrating how workplace leaders can take steps to connect overall workplace mental health and well-being strategies to include suicide prevention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

In 2022, CDC released the Suicide Prevention Resource for Action which details the strategies with the best available evidence to reduce suicide. This Resource for Action can help prioritize suicide prevention activities most likely to have an impact. For example, creating environments that address risk and protective factors where individuals live, work, and play can help prevent suicide. Protective environments that promote positive behaviors and norms may be implemented in places of employment. Such policies and cultural values promote pro-social behavior (such as asking for help), skill building, and positive social norms among all people in the organization or setting.

Workplace Suicide Prevention Task Force

The Workplace Suicide Prevention and Postvention Committee is a group of collaborative, interdisciplinary partners, including employees and workplace leaders with lived experience. In late 2022, the Committee released a white paper, Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention in the Workplace. This paper helps employers support employees living with mental health conditions and understand the legal precedent surrounding best practices for suicide prevention, intervention, crisis response, and postvention (response and activities after a suicide to facilitate healing, mitigate negative effects, and prevent suicide among those at high-risk after exposure to a suicide). This Committee is comprised of academic researchers, business leaders, government officials, and representatives from leading suicide associations. Together, and in full collaboration with members, their aim is to reduce job strain and negative, fear-based, prejudicial and discriminatory thoughts, behaviors, and systems regarding suicide and mental health in the workplace, while serving to share best practices for workplace suicide prevention programs and policies.

The Committee also published additional steps for workplace leaders to consider and are outlined in the U.S. National Guidelines for Workplace Suicide Prevention. Nine best practices to help employers make suicide prevention a health and safety priority at work were developed and include leadership, job strain reduction, communication, self-care orientation, training, peer-support and well-being ambassador, mental health and crisis resources, mitigating risk, and crisis response.

NIOSH Total Worker Health ® Approaches Can Help Safeguard Mental Health

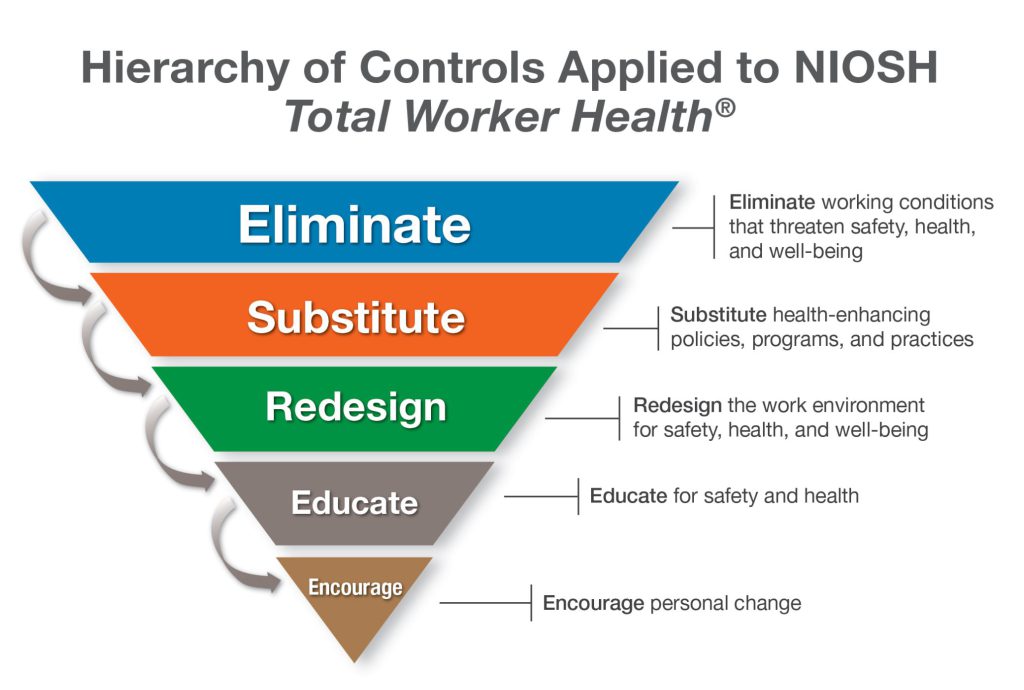

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defines Total Worker Health (TWH) as policies, programs, and practices that protect workers from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention effort. In recognition of the relationship between work and non-work conditions, the TWH approach focuses on how the workplace can reduce risks and enhance overall worker health — going beyond traditional safety and health concerns to address complex challenges like worker mental health or chronic disease.

In light of this, the traditional Hierarchy of Controls was reimagined using NIOSH TWH principals. It includes controls and strategies that more broadly advance worker well-being. Starting at the organizational level and narrowing down to the individual, this hierarchy includes five elements: eliminate, substitute, redesign, educate, and encourage. Unlike traditional occupational safety and health programs, TWH approaches consider the worker health influences that arise outside the workplace, to include interactions between work and non-work demands and circumstances. For example,

- A business could consider eliminating mandatory overtime to allow their workers time to rest.

- A business could redesign job tasks so that mentally or physically heavier tasks are more evenly distributed across the workforce.

- Workplaces could provide workers with education and or training on stress reduction or burnout prevention.

In the context of suicide prevention, employers can eliminate threats to psychological safety (e.g., bullying, toxic management practices, etc.); substitute these unsafe practices with those that promote mental health and protective factors; redesign work culture for optimal well-being including access to mental health care; educate and encourage change through training for psychological safety.[12]

The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization offers the following information for identifying and assisting workers at risk for suicide.

Employers and co-workers should look out for the following signs:

- Expression of thoughts or feelings about wanting to end their life.

- Expression of feelings of isolation, loneliness, hopelessness, or loss of self-esteem.

- Withdrawal from colleagues, decrease in work performance or difficulty completing tasks.

- Changes in behavior, such as restlessness, irritability, impulsivity, recklessness or aggression.

- Speaking about arranging end-of-life personal affairs such as making a will.

- Abuse of alcohol or other substances.

- Depressed mood or mentioning of previous suicidal behavior.

- Bullying or harassment.

- Particular attention should be paid to people who are losing their job.

What co-workers can do if worried about a colleague:

- Express empathy and concern, encourage them to talk, and listen without judgment.

- Ask if there is anyone they would like to call or have called.

- Encourage them to reach out to health or counselling services inside the organization, if available, or otherwise outside the organization, and offer to call or go there together.

- If they have attempted suicide or indicate they are about to intentionally harm themselves, remove access to means and do not leave them alone. Seek immediate support from health services.

What employers or managers can do:

- Provide information sessions for your staff on mental health and suicide prevention.

- Ensure all staff know what resources are available for support

- Foster a work environment in which colleagues feel comfortable talking about problems that have an impact on their ability to do their job effectively.

- Become familiar with relevant legislation.

- Identify and reduce work-related stressors which can negatively impact mental health.

- Design and implement a plan for how to sensitively manage and communicate the suicide or suicide attempt of an employee in a way that minimizes further distress.

WHO SUICIDE AT WORK: Information for employers, managers and employees

Conclusion

The human toll of suicide is increasing. The COVID-19 pandemic added to increased stress, mental health issues, suicidal ideation, attempts, and suicide deaths. This has helped to raise awareness of these issues and demonstrate to workplace leaders that suicide prevention should be a part of health and safety programs and policies. Workplaces are critical in suicide prevention because work-related factors are associated with suicide and because workplaces can be effective suicide prevention sites. Your actions can improve the lives of all your workers and may even save the life of some. Utilize some of the resources in this blog to bring awareness to your workplace today.

If you or someone you know needs help, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. 988 connects you with a trained crisis counselor who can help.

Hope M. Tiesman, PhD, is a Research Epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research. She also sits on the Workplace Suicide Prevention and Postvention Committee.

Jodi Frey, PhD, LCSW-C, CEAP, is a Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of Maryland, in the School of Social Work. She is also the Co-Chair of the Workplace Suicide Prevention and Postvention Committee.

Sally Spencer-Thomas, PsyD, is a Psychologist, Professional Keynote Speaker, Podcaster, and Impact Entrepreneur. She is also the Co-Chair of the Workplace Suicide Prevention and Postvention Committee.

Resources

Suicide Prevention Resource Center

Suicide and Occupation | NIOSH | CDC

Total Worker Health | NIOSH | CDC

Suicide Prevention Resource for Action | Suicide | CDC

Workplace Suicide Prevention – Make suicide prevention a health and safety priority at work

Suicide Prevention Month: Partner Toolkit | Suicide | CDC

Join Us and Help Save a Life – #BeThe1To

References

[1] Thebault R [2019]. Three French executives were convicted in the suicides of 35 of their workers. Washington Post, December 20, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2019/12/20/three-french-executives-were-convicted-suicides-their-workers/

[2] Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD [2013]. Suicide by occupation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 203(6):409-416.

[3] Milner A, Witt K, LaMontagne AD, Niedhammer I [2018]. Psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Occup Environ Med 75(4):245-253.

[4] Choi BK [2018]. Job strain, long work hours, and suicidal ideation in US workers: A longitudinal study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 91(7):865-875.

[5] Niedhammer I, Bertrais S, Witt K. Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: a meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2021;47(7):489–508.

[6] Milner, A., Witt, K., Maheen, H. et al. Access to means of suicide, occupation and the risk of suicide: a national study over 12 years of coronial data. BMC Psychiatry 17, 125 (2017).

[7] Howard, MC, Follmer, KB, Smith, MB, Tucker, RP, & Van Zandt, EC. (2022). Work and suicide: An interdisciplinary systematic literature review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(2), 260–85

[8] Zhao, Y., Richardson, A., Poyser, C. et al. Shift work and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 92, 763–793 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01434-3

[9] Virtanen, Marianna, et al. “Long Working Hours and Depressive Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Studies and Unpublished Individual Participant Data.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, vol. 44, no. 3, 2018, pp. 239–50. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26567002. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

[10] Leach LS, Poyser C, Butterworth P. Workplace bullying and the association with suicidal ideation/thoughts and behaviour: a systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2017;74:72-79.

[11] https://wisqars.cdc.gov/fatal-reports

[12] Lyons TJ, Spencer-Thomas S, Waterhouse H. [2020]. Reduce Workplace Mental Health Hazards With the Hierarchy of Controls for Psychological Safety. Construction Executive, August, https://constructionexec.com/article/reduce-workplace-mental-health-hazards-with-the-hierarchy-of-controls-for-psychological-safety.

Posted on by