An Expanded Focus for Occupational Safety and Health

Posted on by

Work is changing. Technology, globalization, shifts in demographics, and other economic and political forces create new challenges for workers, employers, and those who work to protect them. In a recent commentary in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health we suggest that the field of occupational safety and health (OSH) must also change to meet the needs of the future.

Factors influencing worker health and well-being go beyond traditional OSH concerns (exposures to chemical, physical, or biological agents). They include changing demographic profiles (e.g., more women, immigrant, and older workers and more chronic disease and mental health conditions), varying employment arrangements, increasing work demands, increasing psychosocial hazards, and changing work environments (built and natural) [1,2-8].

This is not an entirely new concept. The World Health Organization (WHO) global model for action, various European efforts for well-being, and the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Total Worker Health® perspective all aim to protect workers and prevent injury and disease, on and off the job. The concept of worker well-being emphasizes quality of life, driven by the relationship between individual worker safety and health and factors both at and outside the workplace, and a desire for workers to thrive and achieve their full potential [5]. Well-being integrates, but goes beyond, the traditional OSH goal of protecting workers from occupational hazards, to include preventing illness and promoting worker health [9,4,5,10-12].

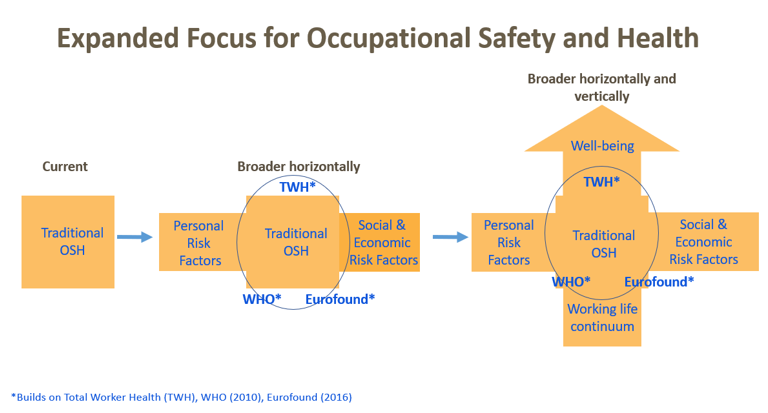

The challenge now is to operationalize and use the concept of well-being and develop transdisciplinary interactions to grow the field. Embracing this paradigm requires a more expansive, systems-thinking approach to better integrate traditional OSH risk factors with personal and socioeconomic factors (horizontal expansion), and broaden the range of factors that impact health (vertical expansion) by considering changes that occur over a working life (see Figure 1 below).

This expansion of the existing paradigm will change how we conduct OSH research, train the future OSH workforce, and design forward-thinking policies and practices within organizations to maximize worker health, safety, and well-being [15]. It is not meant to displace the current members of the OSH community but rather to build a platform on which OSH specialists can work more closely with non-OSH or new OSH specialists to leverage additional success and support for their work. Traditional OSH specialties include occupational medicine and nursing, industrial hygiene, safety epidemiology, toxicology, engineering, occupational psychology, and law. Moving forward, we need a systems-based, more interprofessional approach to identify new skills that support the expanded horizontal and vertical integration. These skills would include areas such as applied economics, sociology, anthropology, human relations, political science, gerontology, informatics, education, program evaluation, business, corporate social responsibility, climate science, architecture, urban planning, and sustainability. While aspects of some of these disciplines already contribute to OSH, the challenge will be to grow, disseminate, and consistently operationalize the contributions.

There is concern that expanding the paradigm to include well-being as an outcome, and more of a “public health approach” than a “labor approach,” could have negative implications. OSH has limited resources, not nearly enough to address problems under the current paradigm [16]. However, if the burden and magnitude of adverse OSH outcomes and the benefits of healthy work and well-being are expansively and clearly described, then the opportunity to leverage more resources to address burden may increase. More to the point, it is no longer effective to think of OSH issues separate from the larger sphere of public health.

To address the growing changes in work, workers, and workplaces, the OSH field will need to develop a broader vision, develop and use new skill sets, and partner with other disciplines and new stakeholders. OSH must be a growing, vibrant discipline. Expanding the vision and growing the field of OSH could produce a healthier workforce and enhance the well-being of nations.

Please share your thoughts about the evolving field of OSH in the comment section below.

Paul Schulte, PhD, is the Director of the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Sarah A. Felknor, MS, DrPH, is the Associate Director for Research Integration at NIOSH.

References

- Howard, J. Nonstandard work arrangements and worker health and safety. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 1–10.

- Dannenberg, A.L.; Frumkin, H.; Jackson, R.J. (Eds.) Making Healthy Places: Designing and Building for Health,Well-Being, and Sustainability; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Chen, P.Y.; Cooper, G.L. (Eds.) Work and well-being. In Well-Being: A Complete Reference Guide; JohnWiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2017; Volume 3.

- Schulte, P.A.; Guerin, R.J.; Schill, A.L.; Bhattacharya, A.; Cunningham, T.R.; Pandalai, S.P.; Eggerth, D.; Stephenson, C.M. Considerations for incorporating “Well-being” in public policy for workers and workplaces.Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e31–e44.

- Chari, R.; Chang, C.C.; Sauter, S.L.; Sayers, E.L.P.; Cerully, J.L.; Schulte, P.; Schill, A.L.; Uscher-Pines, L. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 589–593.

- Moore, P.V. The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts; Routledge: London, UK, 2018.

- Hudson, H.L.; Nigam, J.A.S.; Sauter, S.L.; Chosewood, L.C.; Schill, A.L.; Howard, J. (Eds.) Total Worker Health®; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Schulte, P.A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Butler, C.R.; Chun, H.K.; Jacklitsch, B.; Kiefer, M.; Lincoln, J.; Pendergrass, S.; Shire, J.; Watson, J.; et al. Advancing the framework for considering the effects of climate change on worker safety and health. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2016, 13, 847–865.

- Burton, J. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action for Employers, Workers, Policy Makers, and Practitioners; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Tamers, S.L.; Chosewood, L.C.; Childress, H.; Hudson, H.; Nigam, J.; Chang, C.C. Total Worker Health® 2014–2018: The novel approach to worker, safety, health and well-being evolves. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 10, 321.

- Harrison, J.; Dawson, L. Occupational health: Meeting the challenges of the next 20 years. Saf. Health Work 2016, 7, 143–149.

- Schulte, P.A. An expanded focus for occupational safety and health. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium to Advance Total Worker Health® and Well-being, Bethesda, MD, USA, 10 May 2018.

- Rantenen, J. Research challenges arising from changes in work life. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1999, 25, 473–483.

- Peckham, T.T.; Baker, M.G.; Camp, J.E.; Kaufman, J.D.; Sexias, N.S. Creating future for occupational health. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2017, 61, 3–15.

- Delclos, G. Shaping the Future to EnsureWorker Health andWell-Being: Shifting Paradigm for Research, Training and Policy. Available online: http://grantome.com/grant/NIH/U13-OH011870-01 (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Lax, M.B. The perils of integration wellness and safety and health. New Solut. 2016, 26, 11–39.

Posted on by