Health Equity, Work, and Motor Vehicle Safety

Posted on by

Among U.S. workers, driving a motor vehicle or being exposed to traffic hazards as a pedestrian while at work is a significant risk. In fact, motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) are the leading cause death at work in the United States [1]. Many factors can play a role in work-related MVCs, but have you considered how these factors may have different impacts on workers, depending on their social or demographic characteristics? Given NIOSH’s commitment to advancing health equity, our motor vehicle safety researchers dug into this question.

What do we know about motor vehicle crash disparities in the U.S. population?

Data for the U.S. general population show that the risk of MVCs (and resulting injuries and fatalities) is not evenly distributed across demographic, economic, and social groups [2-3]. In the United States and other countries, the numbers and rates of crashes and fatalities are generally higher for males than for females [4-7]. Compared to all other racial groups, people who identify as American Indian/Alaska Native and Black have the highest MVC fatality rates [3]. Many disparities in MVC risk have been attributed to social determinants of health (SDOH), including differences in the access to and quality of healthcare and education, economic stability, the social and community environment, and the neighborhood and built environment [9].

What’s the role of work in motor vehicle crash disparities?

Like MVCs in the general population, there are also disparities in the risk of work-related MVCs by sex, age, race, and ethnicity. For example, older workers (ages 65+) have the highest fatality rates [3-5,8]. However, published research on the contribution of work factors to MVC disparities is limited. To understand and address the role of work in MVC disparities, researchers and policymakers may consider the broad social, political, and organizational environments that may foster and perpetuate these disparities.

What a review of literature on disparities revealed

A recent commentary by NIOSH researchers [10] describes how work-related motor MVC disparities are often related to:

- what kinds of work people do,

- the type of employment arrangements they have,

- the way employers implement occupational safety and health (OSH) policies,

- how employees commute to and from work, and

- where employees live.

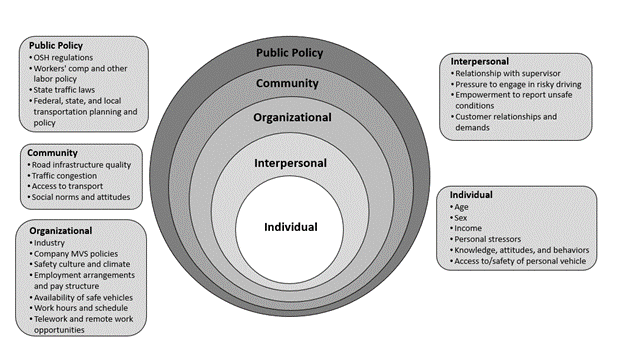

NIOSH researchers reviewed international literature on the current state of disparities in work-related MVCs. They applied the Social–Ecological Model (SEM) to organize potential underlying causes of disparity, primarily in the U.S. context, at five levels—individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy. Factors that might contribute to disparities in work-related MVCs are listed in Figure1.

Figure 1. The social–ecological model applied to the risk of work-related motor vehicle crashes and injury. (Adapted from Reference [11]).

The SEM is a useful framework to illustrate how individual factors (the focus of most work-related MVC research) are embedded within larger circles depicting the influence of interpersonal relationships, organizational factors, community-level factors, and public policy. Organizational factors are especially relevant to work-related MVCs, as they include the employer’s safety culture and policies, employment arrangements, and industry-specific norms and practices that might inhibit motor vehicle safety efforts and influence individual driving behaviors and decisions. This model is helpful to study equity and work-related MVCs, as it illustrates the breadth and interaction of work and societal factors outside an individual’s control that can create disparities.

Commuting: an area of need for research and intervention

Commuting safety is not often discussed in the context of OSH, yet commuting opportunities and behaviors may place some workers at greater risk of a MVC or pedestrian injury. Differences in commuting and associated risks may be linked to income, rural or urban residence, employment arrangements, ability to work from home, access to a vehicle, access to public transportation, and road infrastructure quality. For lower-income workers and those who belong to communities of color, commuting time (and, hence, exposure to a possible crash or pedestrian injury) is greater due to many factors, including lack of affordable housing near work or living in a household without a car [12-13]. Lower-income workers without access to a car spend more time as pedestrians, walking to and between transit modes, and waiting at transit stops. Workers with non-standard or weekend schedules are further disadvantaged because of reduced transit options at off-peak hours [14]. Travel to and from work during off-peak hours may also increase MVC risk for pedestrians, as 73.6% of pedestrian fatalities in the United States in 2020 occurred between the hours of 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. [2]. Research is needed to better understand the impacts of SDOH and work on commuting crashes and injuries.

Understanding and addressing inequities in work-related MVCs.

Better data and more research are needed to understand and respond to inequities for pedestrian workers, workers from historically marginalized communities, workers not adequately covered by employer policies and safety regulations, and workers with overlapping vulnerabilities (falling into two or more at-risk groups) [15]. In their call for equity-centered occupational motor vehicle safety surveillance and research, the authors highlight the need to improve existing data collection systems by adding data items that would help us to better understand underlying causes of work-related MVCs and by applying new research methodologies to analyze data. The following actions may be first steps in positioning researchers to identify and act upon inequities in work-related motor vehicle safety [10].

Surveillance

-

- Collect data on U.S. worker populations who may experience inequities in transportation, such as persons with disabilities.

- Expand data linkage and data sharing across crash, work-related injury, and public health data systems.

- Incorporate income and other socioeconomic data into these data systems.

- Collect and use the most appropriate exposure-based denominator data in the calculation of rates, such as vehicle miles traveled or hours of driving by workers.

- Identify commuting crashes in reports and national data systems to understand who is most affected.

Research

-

- Expand analyses by sex and age to understand underlying crash and injury risk factors, going beyond biological factors.

- Explore underlying reasons for racial and ethnic disparities in work-related MVCs.

- Include commuting crashes in research on work-related MVCs.

- Conduct additional research on pedestrian struck-by incidents at work.

- Increase geographic scope of research to include low- and middle-income countries.

- Where possible, include mixed methods and variables at all levels of the SEM in your research, to account for the likely multi-level sources of disparities and inequities.

Advancing our understanding of disparities in work-related MVCs means moving beyond the examination of individual characteristics and driving behaviors. We must understand the broader social and institutional contexts in which MVCs occur. Work-related MVC disparities are often related to what kinds of work people do, the type of employment arrangements they have, the way employers implement OSH policies, how employees commute to and from work, and where employees live.

Interventions to address work-related MVC inequities are also needed, especially those that are implemented at the organizational, community, and public policy levels of the SEM. Interventions that span multiple levels of the SEM will be more likely to remedy inequities for groups at higher risk for transportation injuries, including workers in low-income categories [16].

Let’s continue the conversation!

NIOSH’s Center for Motor Vehicle Safety conducts research and develops strategies to reduce crashes and injuries for all people who drive as part of their job. We are interested to know what equity-related crash or injury research you are doing that considers the role of work. What are your thoughts on policies and interventions that can protect everyone who drives as part of their job? Please let us know in the comments!

Kyla Hagan-Haynes is the Director of the Center for Motor Vehicle Safety, the Assistant Coordinator for the Traumatic Injury Cross-Sector Program and a Research Epidemiologist in the Western States Division.

Rosa Rodríguez-Acosta is a Research Epidemiologist in the Division of Safety Research.

Rebecca Knuth is the Lead Health Communications Specialist for the Division of Safety Research and for the Center for Motor Vehicle Safety.

Stephanie Pratt is the retired Director of the Center for Motor Vehicle Safety and currently a road safety consultant for NIOSH.

References

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table A-2. Fatal Occupational Injuries Resulting from Transportation Incidents and Homicides, All United States, 2011–2020; Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts Annual Report Tables. Available online: https://cdan.nhtsa. gov/tsftables/tsfar.htm# (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Glassbrenner, D.; Herbert, G.; Reish, L.; Webb, C.; Lindsey, T. Evaluating Disparities in Traffic Fatalities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income (DOT HS 813 188); National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Green, M.K.; Harrison, R.; Kathy, L.; Nguyen, C.B.; Towle, M.; Schoonover, T.; Bunn, T.; Northwood, J.; Pratt, S.G.; Myers, J.R. Occupational highway transportation deaths—United States, 2003–2008. MMWR 2011, 60, 497–502.

- Pratt, S.G.; Rodríguez-Acosta, R.L. Occupational highway transportation deaths among workers aged ≥55 years—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR 2013, 62, 653–657.

- Sultana, S.; Robb, G.; Ameratunga, S.; Jackson, R.T. Non-fatal work-related motor vehicle traffic crash injuries in New Zealand: Analysis of a national claims database. N. Z. Med. J. 2007, 120, 1–13.

- Driscoll, T.; Marsh, S.; McNoe, B.; Langley, J.; Stout, N.; Feyer, A.-M.; Williamson, A. Comparison of fatalities from work related motor vehicle traffic incidents in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. Inj. Prev. 2005, 11, 294–299. [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.K.; Olson, R.; Karr, J.; Zoller, E.; Cain, D.; Douglas, J.P. Elevated occupational transportation fatalities among older workers in Oregon: An empirical investigation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 53, 28–38. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). Available online: https://www.cdc. gov/socialdeterminants/about.html (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Pratt, S., & Hagan-Haynes, K.. Applying a health equity lens to work-related motor vehicle safety in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health, 2023, 20(20), 6909.

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. DP04: Selected Housing Characteristics (2019: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles). Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?tid=ACSDP5Y2019.DP04&hidePreview=true (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Commuting in America 2021: The National Report on Commuting Patterns and Trends (Brief21.2, Vehicle Availability Patterns and Trends); AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Kaufman, S.M.; Moss, M.L.; Hernandez, J.; Tyndall, J. Mobility, Economic Opportunity and New York City Neighborhoods; New York University, Rudin Center for Transportation: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, American Society of Safety Engineers. Overlapping vulnerabilities: the occupational safety and health of young workers in small construction firms. By Flynn MA, Cunningham TR, Guerin RJ, Keller B, Chapman LJ, Hudson D, Salgado C. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH), Publication No. 2015- 178, 2015.

- Baron, S.L.; Beard, S.; Davis, L.K.; Delp, L.; Forst, L.; Kidd-Taylor, A.; Liebman, A.K.; Linnan, L.; Punnett, L.; Welch, L.S. Promoting integrated approaches to reducing health inequities among low-income workers: Applying a social ecological framework. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 539–556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Posted on by