Social Connection and Worker Well-being

Posted on by

In May, the U.S. Surgeon General, Vice Admiral Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, released Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community calling for a whole-of-society approach to address the epidemic of loneliness and isolation.1 Below we briefly highlight information from the Advisory and its implications for worker well-being.

Based on decades of research examining the importance of social connection to individual and community health, the Advisory refers to multidisciplinary evidence indicating that social connection can predict longevity and well-being, while loneliness and social isolation are predictors of poor health and premature death.1(p.23) In fact, the Advisory points out that the benefits of social connection extend beyond individual health to community-level outcomes, such as greater economic prosperity, reduced crime and community violence, and better disaster preparedness and recovery among communities.

What Is Social Connection and How Is It Related to Health?

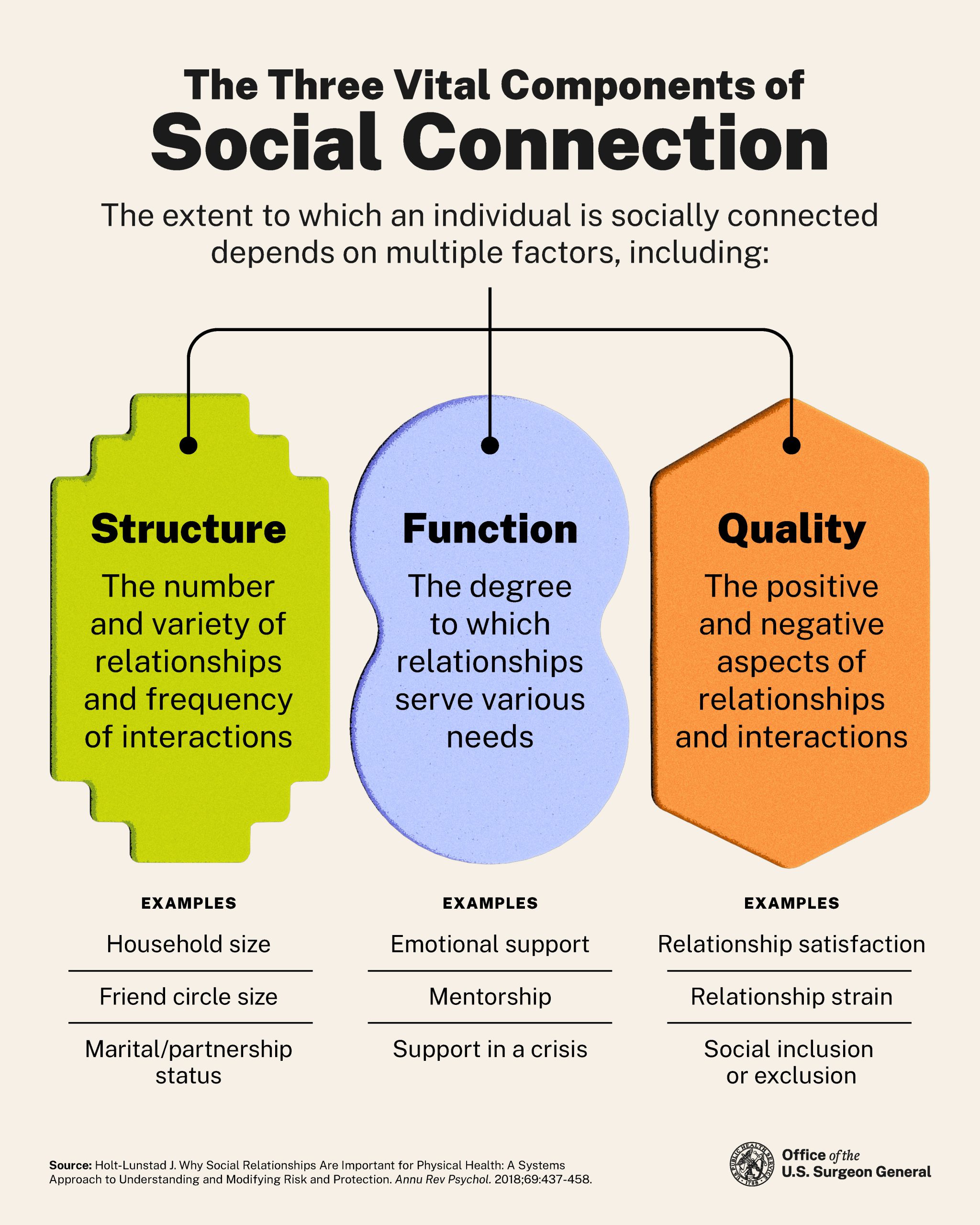

The Advisory refers to social connection as, “a continuum of the size and diversity of one’s social network and roles, the functions these relationships serve, and their positive or negative qualities.”1(p.7) For workers in particular, social connection may be influenced at work and away from work by the structure (e.g., number, variety of and frequency of work and nonwork interactions), function (e.g., supervisor, co-worker, and peer support, mentorship), and quality of social relationships (e.g., degree of positive work and nonwork relationships and interactions) 1,2 (see figure 1). Whereas, social connectedness is, “the degree to which any individual or population might fall along the continuum of achieving social connection needs,”1(p.7) belonging is defined as “a fundamental human need,” and refers to, “the feeling of deep connection with social groups [e.g., family, colleagues], physical places [e.g., workplaces], and individual and collective experiences [e.g., work evaluation and experience].” 1(p.7) Conversely, loneliness is an indicator of social connection that is described as, “a subjective distressing experience that results from perceived isolation or inadequate meaningful connections, where inadequate refers to the discrepancy or unmet need between an individual’s preferred and actual experience.”1(p.7)

According to the Advisory, social connection influences individual health via three important pathways, each with their own processes: biological, psychological, and behavioral.1,3 Research shows that social connection can improve our individual health and well-being. On the other hand, loneliness and an inadequacy of healthy connections may increase the risk for physical, cognitive, and emotional health concerns such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, dementia, and suicide, and substance abuse.4 The Advisory points out that increasing social connection by small increments can improve health and reduce the risk for illness and mortality.1(p.67) Loneliness is a significant work-related concern, as is subsequently discussed in this blog.

What Are Current Trends Related to Social Connection and Loneliness?

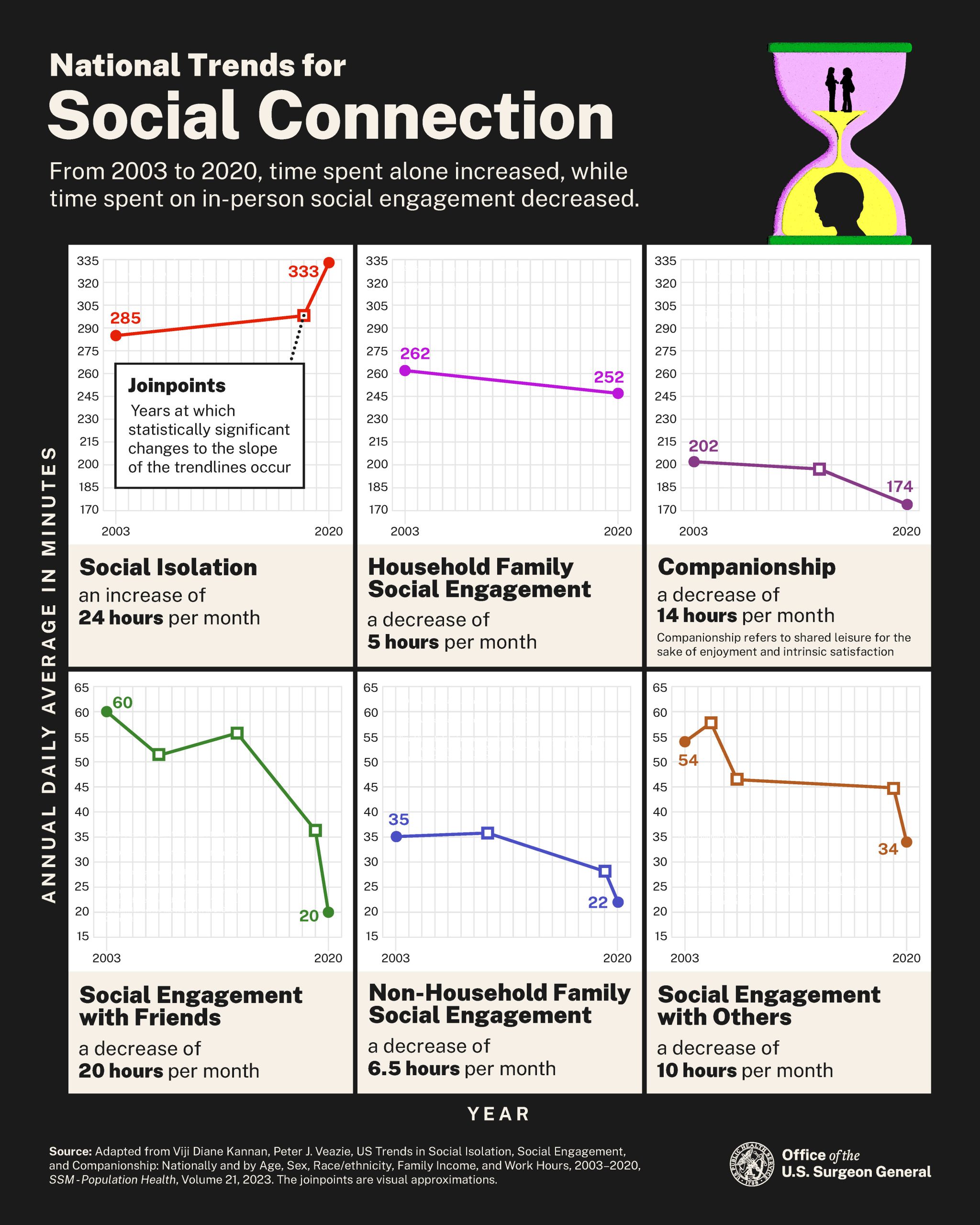

Over the past few decades, trends in the United States show that companionship and engagement with friends and family have declined while social isolation has increased 5 (see figure 2). Trust in others and in institutions, an indicator for social connectedness, is reported to be on a historic decline among Americans.6

Approximately half of U.S. adults report experiencing loneliness.7 Loneliness affects people from all age groups, socioeconomic conditions, and geographies. Groups with higher prevalence of loneliness and isolation include those with poor physical and mental health, younger and older adults, single parents, those who live alone or in rural areas, individuals from ethnic and racial minority groups, LGBTQ+ individuals, and lower wage earners.1(p.19)

If fact, the loneliest workers tend to be those with lower incomes, newer in their employment, and engaged in gig work, according to a study by Cigna.8 Further, excessive remote work was correlated with greater loneliness while having satisfactory in-person interactions was linked with less loneliness. Loneliness can have significant financial costs for employers, primarily through absenteeism. Employers faced an estimated $154 billion in 2019 from lost productivity, and employees who had reported feeling lonely missed 5.7 additional days than those who hadn’t.9

What could be driving these downward trends in social connection? The Advisory points to declining social participation, demographics, reduced community involvement, and use of technology as potential factors. For example, Americans are living alone today at more than twice the rate than in 1960, family size and marriage rates are declining, and community involvement (e.g., participation labor unions and faith organizations) has been on the decline since the 1970s.1(pp.15-16) Although these links are not causal, it is likely that these societal changes have served to increase isolation and loneliness and decrease social connectedness among Americans.

What Is the Relationship Between Social Connection and Worker Well-being?

The Advisory calls for a whole-of-society, cross-sector approach to recognize and address social isolation and loneliness as a public health concern by incorporating social connection into the social infrastructure, policies, and programs that shape communities and population, as well as individual, health, and well-being. Researchers and experts in occupational safety and health (OSH) also suggest a broader systems thinking approach to address worker well-being and workers’ opportunities for health outside of work.10 Traditionally, the OSH field focused on addressing risk factors for worker health using the hierarchy of controls, which examines the immediate work context. Strategies for worker safety and health were implemented at the organization level and/or at the worker level. Over the past two decades, however, the paradigm has shifted toward a broader approach to OSH. This shift has been driven by contemporary factors such as the changing nature of work, the workforce, and the workplace; the recognition that work is a major determinant of health; and the recognition that work and nonwork factors interact independently and collectively to influence work and workers’ health.11,12 Aligning with this broader approach, NIOSH is promoting the integration of health protection (i.e., prevention of work-related disease, injury, disability) with activities that influence worker well-being both within and outside the context of work (i.e., worker voice, positive work-related relationships, job flexibility).13 Thus, the design of work, as it governs our ability for healthy social connection, is an important consideration.

While the evidence for addressing work-related factors to improve worker well-being is becoming more established, research to prevent loneliness and promote social connectedness at work, especially across individual levels, organizational levels, and in the design of work, is in a nascent stage.14-16 The U.S. Surgeon General’s latest advisories on loneliness, mental health, and well-being in the workplace shine the light on the need to better understand the relationship between social connection and work, as well as the role that researchers, employers, and workers can play in advancing overall worker well-being.17,18

What Does the Advisory Recommend for Promoting Social Connectedness at Work?

The Advisory calls on many groups, such as employers and researchers, to engage and lead efforts to prioritize and promote social connectedness. In particular, centered on worker voice and equity, the Surgeon General recommends the following actions for workplaces:

- Make social connection a strategic priority in the workplace.

- Train, resource, and empower leaders and managers to implement and continually improve programs and practices that foster social connection in the workplace.

- Leverage existing resources to educate the workforce about the importance of social connection for worker well-being.

- Create a workplace culture that fosters inclusion and belonging.

- Establish policies and practices that protect workers’ abilities to nurture their relationships outside work, while respecting boundaries between work and nonwork time.

- Consider the opportunities and challenges that various work arrangements pose to workers’ ability to connect with others at work and outside of work. Evaluate how such policies and practices can be applied equitably across the workforce.

What Are Some Existing Efforts to Promote Social Connection at Work?

Increased awareness of the loneliness epidemic and the health impact of inadequate social connection, especially through the setting of national, state, and local priorities will likely be met with intervention research for increasing social connectedness at work.

Meanwhile, we can draw from many robust and related organizational strategies that are effective in promoting worker well-being:

- Train managers and supervisors to be supportive with regard to employees’ family-related needs.19,22

- Implement worker well-being strategies and supports that are equitable and inclusive of workers with unique needs and life demands.21

- Ensure worker autonomy and worker voice to help foster a sense of belonging at work.22

- Improve the design of work, management practices, organizational policies, and the physical and psychosocial environment.16,22

NIOSH’s Total Worker Health® and Healthy Work Design and Well-being programs support these approaches.13,21 Work is a well-recognized social determinant of health and both programs acknowledge that organizational policies, working conditions, and job tasks must be designed to protect the well-being—and inherently social connections—of workers and their families in equitable ways.23 Aligned with the recommendations for workplaces from the Surgeon General’s Advisory, these NIOSH programs can help employers implement organizational practices and policies that promote worker well-being through meaningful social connection at work and away from work. Further, these programs seek to expand the body of scientific literature that advances worker safety, health, and well-being, and that empowers employers and workers to create safer and healthier workplaces.

The ten NIOSH Centers of Excellence for Total Worker Health, located throughout the United States, are hubs for Total Worker Health-related research and practice. Together, they address emergent issues impacting the workforce; develop science-based, practical solutions to complex OSH problems; and act as a resource for worker well-being. The heightened need to tackle the loneliness epidemic and improve social connectedness promises to be a focus moving forward.

Food for Thought

Do you have co-workers with whom you feel closely connected? How does having work friends affect your daily work experience?

As an employer, how are you fostering social connectedness within your organization?

As an organizational leader, what policies and programs have you established to ensure your workforce can develop social connections at work and outside work?

As a researcher, how is your work contributing to the understanding of best practices on building social connectedness at work?

Anjali Rameshbabu, PhD, is Senior Research Project Manager at the Oregon Healthy Workforce Center, a NIOSH-funded Center of Excellence for Total Worker Health.

CDR Heidi Hudson, MPH, is Coordinator for Research Development and Collaboration for the NIOSH Total Worker Health Program and Assistant Coordinator for the NIOSH Healthy Work Design and Well-being Cross-sector Program.

References

- USPHS, Office of the Surgeon General [2023]. Advisory: the healing effects of social connection. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/connection/index.html#advisory.

- Holt-Lunstad J [2018]. Why Social Relationships Are Important for Physical Health: A Systems Approach to Understanding and Modifying Risk and Protection. Annu Rev. Psychol 69:437-458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

- Holt-Lunstad J [2021]. The Major Health Implications of Social Connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science,30(3):251-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721421999630

- Hawkley LC [2022]. Loneliness and health. Nat Rev Dis Primers 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00355-9.

- Kannan VD, Veazie PJ [2022]. US trends in social isolation, social engagement, and companionship—nationally and by age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and work hours, 2003–2020. SSM Popul Health 21:101331, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101331.

- Davern M, Bautista R, Freese J, Morgan S, Smith T [n.d.]. General social surveys, 1972–2021 Cross-section [machine-readable data file, 68,846 cases]. In: NORC at the University of Chicago, ed. Chicago: NORC at the University of Chicago.

- Bruce LD, Wu JS, Lustig SL, Russell DW, Nemecek DA [2018]. Loneliness in the United States: a 2018 national panel survey of demographic, structural, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics. Am J Health Promot 33(8):1123–1133.

- Cigna [2020]. Loneliness and the Workplace: US 2020 Report. https://www.cigna.com/static/www-cigna-com/docs/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/combatting-loneliness/cigna-2020-loneliness-report.pdf

- Bowers A Wu J, Lustig S, Nemecek D [2022]. Loneliness influences avoidable absenteeism and turnover intention reported by adult workers in the United States. J Organ Effectiveness: People Performance, 9(2): 312–335, https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2021-0076.

- Schulte P, Sauter S [2021]. Work and well-being: the changing face of occupational safety and health. NIOSH Science Blog. June 7, https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2021/06/07/work-and-well-being/.

- Tamers SL, Streit J, Pana-Cryan R, Ray T, Syron L, Flynn MA, Castillo D, Roth G, Geraci C, Guerin R, Schulte P, Henn S, Chang CC, Felknor S, Howard J [2020]. Envisioning the future of work to safeguard the safety, health, and well-being of the workforce: a perspective from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Am J Ind Med 63(12):1065–1084, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23183.

- Schulte P, Pandalai S [2019]. Interrelationships of occupational and personal risk factors in the etiology of disease and injury. In: Hudson et al., eds. Total worker health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- NIOSH [2021]. Total worker health program. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, https://www.cdc.gov/NIOSH/twh/.

- Adams JM [2019]. The value of worker well-being. Public Health Reports 134(6):583–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354919878434.

- McLellan RK [2017]. Work, health, and worker well-being: roles and opportunities for employers. Health Affairs 36(2):206–213, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1150.

- Fox KE, Johnson ST, Berkman LF, Sianoja M, Soh Y, Kubzansky LD, Kelly EL [2022]. Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: a systematic review. Work & Stress 36(1):1–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1969476.

- USPHS, Office of the Surgeon General [2023]. Current priorities of the U.S. Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/index.html.

- USPHS, Office of the Surgeon General [2022]. Framework for workplace mental health & well-being. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/workplace-well-being/index.html.

- Mohr C, Hammer L, Dimoff J, Lee JD, Arpin SN, Umemoto S, Allen S, Brockwood K, Bodner T, Mahoney L, Dretsch M [2023]. How workplaces can reduce employee loneliness: evidence from a military supportive-leadership training intervention. Preprints, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8g4sp.

- Crain TL, Stevens SC [2018]. Family‐supportive supervisor behaviors: a review and recommendations for research and practice. J Organ Behav 39(7):869–888, https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2320.

- NIOSH [2019]. Healthy work design and well-being program. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/programs/hwd/default.html.

- National Occupational Research Agenda Healthy Work Design and Well-being Cross-sector Council [2019]. National occupational research agenda for healthy work design and well-being. https://www.cdc.gov/nora/councils/hwd/pdfs/Final-National-Occupational-Research-Agenda-for-HWD_January-2020.pdf.

- Wipfli B, Wild S, Richardson, DM, Hammer, L [2021]. Work as a Social Determinant of Health: A Necessary Foundation for Occupational Health and Safety. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 63(11), e830–e833. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002370

Posted on by