Precarious Work, Job Stress, and Health-related Quality of Life

Posted on byQuality of work is a central issue in understanding worker well-being [1]. Work is changing due to several factors including technology and demographics and so is the way work is organized and designed. These changes have led to non-standard work arrangements, like gig work, resulting in an increased prevalence of precarious work [2]. While there is no standardized definition of precarious work it can be broadly defined as uncertain, unstable and insecure work in which workers, as opposed to businesses or the government, bear the risks associated with work and receive limited social benefits and statutory protections [3-7]. A NIOSH study constructed a work precariousness scale to address the gap in precarious work research in the United States [8].

Background

Precarious work affects adverse health and well-being through three main pathways [9]. First, precarious work exposes workers to harmful and unsafe working conditions endangering their physical health. Second, precarious work may limit workers’ control over their professional and personal lives, leading to psychosocial stress. Finally, some of the most critical consequences of precarious work are social and economic deprivation, affecting overall well-being. Studies have documented the health, including mental health, consequences of some aspects of precarious work like job insecurity and temporariness [10-15]. Because there is no standard definition there is no unique way to measure precariousness, making it difficult to capture its characteristics and compare studies that assessed precarious work across countries [10, 16-18]. Some aspects of precarious work are captured by other quality-of-work constructs, for example, contingent work and non-standard work arrangements. The concepts of precarious work, contingent work, and work arrangements are not mutually exclusive; for example, some workers in standard work arrangements may experience unfair treatment, a characteristic of precarious work. However, research on non-standard work arrangements rarely addresses concerns regarding precarious work in the United States [19, 20].

Partially due to the lack of standardized definition, it is challenging to estimate the prevalence of precarious work. While efforts are underway to improve data collection, the majority of the available surveys fail to provide data that fully characterizes these concepts and their health and well-being consequences.

Carefully calibrated and disaggregated metrics are needed to better understand the determinants and effects of precarious work. Few precarious work constructs and models have been proposed, mainly in the European context. For example, Amable et al. and Lewchuk et al. considered precarious work as a multidimensional construct, defined across four dimensions of continuity (i.e., temporality), vulnerability (i.e., powerlessness), protection (i.e., limited fringe benefits), and income insufficiency (i.e., low level of earnings) [21, 22]. In another study, Benach et al. classified precarious work based on employment insecurity, individualized bargaining relations between workers and employers, low wages and economic deprivation, limited workplace rights and social protection, and powerlessness to exercise workplace rights [9].

The NIOSH Study

Based upon the employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES) developed by Amable et al. [21], the NIOSH study measured work precariousness among US workers for the first time [8]. Besides measuring precariousness, the study also contributes to understanding precarious work’s health consequences by assessing the individual relationships between

- precarious work and job stress,

- precarious work and unhealthy days (days in poor physical and mental health), and

- precarious work and days with reduced productive functioning (days with activity limitations).

The study used pooled cross-sectional data from the NIOSH‐sponsored Quality of Work-Life module of the General Social Survey (GSS‐QWL) for the years 2002 – 2018. The analyses show how work precariousness has changed over the years and how various work arrangements and industries differ in their share of precarious work. A total of twenty-two survey items were used to construct four different components of the precariousness scale

- temporariness,

- disempowerment,

- vulnerability, and

- wages.

Table 1: Components and variables of our precariousness scale.

| Components | Variables |

| Temporariness | Job security: The job security is good.

Labor force status: Last week were you working full time, part time, going to school, keeping house, or what? Salaried or wage earner: In your main job, are you salaried or paid by the hour? Job tenure: How long in the current job? |

| Disempowerment | Decision making: In your job, how often do you take part with others in making decisions that affect you?

Job schedule: How often are you allowed to change your starting and quitting times on a daily basis? Union membership: Do you or your spouse belong to any union? Employer and employer relation: In general, how would you describe relation in your work place between management and employees? Help with equipment: I receive enough help and equipment to get the job done. Must work: When you work extra hours on your main job, is it mandatory (required by your employer)? Developing opportunity: I have an opportunity to develop my own special abilities. |

| Vulnerability | Respect at workplace: At work, people are treated with respect.

Trust towards management: I trust the management at the place where I work. Productive: Conditions on my job allow me to be about as productive as I could be. Age discrimination: Do you feel in any way discriminated against on your job because of your age? Race discrimination: Do you feel in any way discriminated against on your job because of your race or ethnic origin? Safe team: Where I work, employees and management work together to ensure the safest possible working conditions. |

| Wages | Financial situation: So far as you and your family are concerned, how would you say your financial situation is.

Gross family income: Inflation-adjusted family income in constant dollars. Family income satisfaction: Compared with American families in general, would you say your family income is comparable. Fringe benefits: My fringe benefits are good. Chances of promotion: The chances for promotion are good. |

Scores from these individual categories were combined to construct an overall precariousness score. Finally, associations of higher precarious scores with elevated job stress, increased unhealthy days, and

increased days of reduced productive functioning were identified. The analyses reported that the percentages of highly precarious work increased from 2002 (32.12%) to 2010 (35.37%) and then decreased in 2014 (30.96%). Precarious work was more common among

- workers in the age group of 25–34 years (39.4%),

- multi‐racial workers (52.3%),

- Black workers (46.0%), and

- Hispanic workers (44.8%).

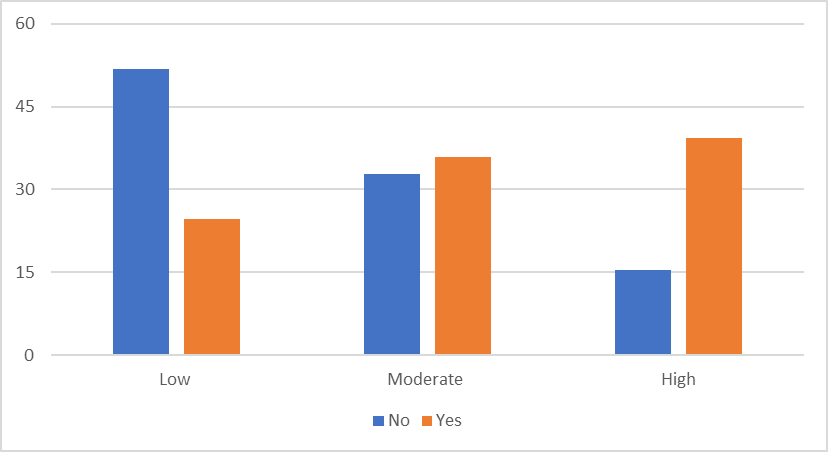

The study also found that workers engaged in highly precarious work were 57% more likely to report experiencing job stress than those engaged in low precarious work.

From the associations between unhealthy days and work precariousness, the study found that individuals in highly precarious work reported more unhealthy days (0.4 days more within 30 days) than those not engaging in precarious work. From the associations between reduced productive functioning and work precariousness, the study found that individuals in highly precarious work reported experiencing a higher number of days of activity limitation (1.2 more days within 30 days period) than those in low precarious work.

Next Steps

Outcomes of this study provide support for the precariousness scale developed by NIOSH and the scale’s suitability for assessing the health‐related quality of life of workers in different work arrangements. This understanding can help us develop effective interventions to reduce the prevalence of precarious work. Ongoing assessment of the scale’s validity with other data sets capturing both similar and additional variables and components of the scale will allow for further development and exploration of the scale. Future research should examine the psychometric properties of the scale and apply it to other national‐level data to explore the robustness of the scale.

Anasua Bhattacharya, PhD, is an Economist in the Economic Research and Support Office of NIOSH.

Tapas Ray, PhD, is an Economist in the Economic Research and Support Office of NIOSH.

References

- Chari R, Chang CC, Sauter S, Petrun Sayers E, Cerully JL, Schulte P, Schill AL, Uscher-Pines L. Expanding the Paradigm of Occupational Safety and Health, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine: July 2018 – Volume 60 – Issue 7 – p 589-593 doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001330

- Ray TK, Kenigsberg TA, Pana-Cryan R. Employment arrangement, job stress, and health-related quality of life. Safety Science; 2017, Part A 100, pp. 46-56. elsevier.com/locate/ssci doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2017.05.003

- Rodgers G. Precarious work in Europe: the state of the debate. In: Rodgers G, Rodgers J eds. Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation. Geneva, SZ: International Institute for Labour Studies, International Labour Organization; 1989.

- Kalleberg A. Nonstandard employment relations: part‐time, temporary, and contract work. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:341‐

- Vosko L. Managing the Margins: Sex, Ctizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Kalleberg A, Hewison K. Precarious work and the challenge for Asia. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013;57(3):271‐

- Hewison K. Precarious Work. In: Edgell S, Gottfried H, Granter E, eds. The Sage Handbook of the Sociology of Work and Employment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2016. Bhattacharya A, Ray T. Precarious work, job stress, and health-related quality of life. Am. J. Ind. Med.2021;64, 310–319. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23223

- Bhattacharya A, Ray T. Precarious work, job stress, and health-related quality of life. J. Ind. Med.2021;64, 310–319. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23223

- Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, Vanroelen C, Tarafa G, Muntaner C. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:229‐+ ` .

- Moscone F, Tosetti E, Vittadini G. The impact of precarious employment on mental health: the case of Italy. Soc Sci Med. 2016;158: 86‐ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.008

- arrieri V, Novi CD, Jacobs R, et al. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Insecure, Sick and Unhappy? Well‐Being Consequences of Temporary Employment Contracts Factors Affecting Worker Well‐Being: The Impact of Change in the Labor Market. Washington DC: GAO, US Government Accountability Office; 2014:157‐

- Robone S, Andrew J, Nigel R. Contractual conditions, working conditions and their impact on health and well‐being (Springer; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gesundheitsökonomie (DGGÖ)). The European Journal of Health Economics. 2011;12(5):429‐

- Quesnel‐Vallee A, DeHaney S, Ciampi A. Temporary work and depressive symptoms: a propensity’ score analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70(12):1982‐

- Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Joensuu M, Virtanen P, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(3):610‐

- Waenerlund AK, Virtanen P, Hammarström A. Is temporary employment related to health status? Analysis of the Northern Swedish cohort. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:533‐

- From precarious work to decent work: Outcome document to the workers’ symposium on policies and regulations to combat precarious employment. 2011. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—ctrav/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_179787.pdf. Accessed on September 15, 2020.

- Ray T, Kenisgsberg T, Pana‐Cryan R. Employment arrangement, job stress, and health‐related quality of life. Safety Science. 2017;100: 46‐

- Kreshpaj B, Orellana C, Burström B, et al. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46:235‐

- United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) Contingent workforce: Size, Characteristics, Earnings, and Benefits. Washington DC: Office GA; 2015.

- Katz L, Krueger A The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. In: Research NBoE. Cambridge, MA, 2016.

- Amable M, Benach B, Gonzalez S. Precariedad laboral y su repercussion sobre la salud: conceptos y resultados preliminares de un estudio multimétodos. Arch Prev Riesgos Labor. 2001;4(4): 169‐

- Lewchuk W, Wolff AD, King A, et al. From job strain to employment strain: health effects of precarious employment. Just Labour. 2003;3: 23‐

Posted on by