Suicide Prevention for Healthcare Workers

Posted on byIf you or someone you know needs support now,

call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.

988 connects you with a trained crisis counselor who can help.

Each September the nation comes together to mark Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, an annual observance highlighting the importance of this growing public health issue. This also serves as a time to educate the public about the role they can play in keeping themselves and those around them feeling supported and connected.

Suicide is a complex public health problem with no single cause. Mental health—which includes a person’s psychological, emotional, and social well-being and affects how one feels, thinks, and acts—can be associated with suicide, but other factors play a role as well. These factors can include relationship problems, substance use, physical health challenges, job stressors, and financial and legal problems. Suicide can also be an outcome of poor mental health.

There has been an increase in suicidal ideation (suicide-related thoughts) and suicide mortality (death caused by injuring oneself with the intent to die) in the U.S. over the last three decades. The overall suicide rate in the U.S. has increased by 32% since 1999.[1] In 2019:

- 12 million American adults seriously thought about suicide.[1]

- 47,511 people died by suicide, which is about 1 suicide every 11 minutes.[1]

- Suicide was the 10th leading cause of death overall.[2]

Healthcare Workers are Vulnerable to Suicide

Some occupations are known to have higher rates of suicide than others (see related blogs). Job factors — such as low job security, low pay, and job stress [3-5] —can contribute to risk of suicide, as can easy access to lethal means among people at risk—such as medications or firearms.[3,6] Other factors that can influence the link between occupation and suicide include sex, socioeconomic status, the economy, cultural factors, and stigma.[3,4,6,7]

Healthcare workers have historically been at disproportionate risk of suicide, due to a variety of factors, including:

- difficult working conditions, such as long work hours, rotating and irregular shifts,

- emotionally difficult situations with patients and patient’s family members,

- risk for exposure to infectious diseases and other hazards on the job, including workplace violence,

- routine exposure to human suffering and death, and

- access to lethal means such as medications and knowledge about using them.

In 2019, a large review of scientific studies was conducted to address conflicting data on the nature of suicide among healthcare workers. Over 60 studies were included in the analysis. The researchers found that physicians were at a significant and increased risk for suicide, and female physicians were at particularly high risk. There were insufficient studies and data on other healthcare workers to make any other conclusions.[8]

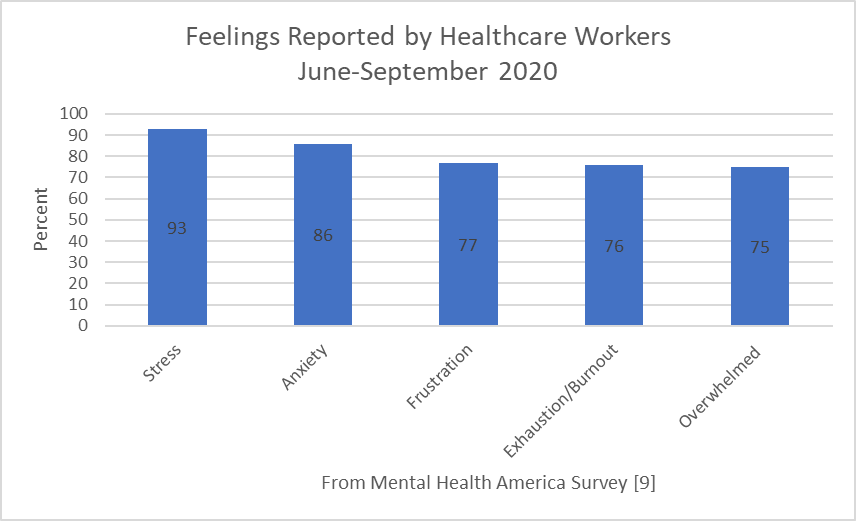

The COVID-19 pandemic has also had a major impact on those healthcare workers on the frontlines. The well-publicized suicide of Dr. Lorna Breen underscores the risk for suicide among physicians who are working on the frontlines of the pandemic. Yet, it isn’t just physicians – other health workers are also at risk. Mental Health America conducted a study of healthcare workers – including nurses, community-based healthcare workers, doctors, support staff, EMT/paramedics, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners – from June-September 2020. The survey revealed: 93% of health care workers were experiencing stress, 86% reported experiencing anxiety, 77% reported frustration, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 75% said they were overwhelmed.[9]

The COVID-19 pandemic has also had a major impact on those healthcare workers on the frontlines. The well-publicized suicide of Dr. Lorna Breen underscores the risk for suicide among physicians who are working on the frontlines of the pandemic. Yet, it isn’t just physicians – other health workers are also at risk. Mental Health America conducted a study of healthcare workers – including nurses, community-based healthcare workers, doctors, support staff, EMT/paramedics, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners – from June-September 2020. The survey revealed: 93% of health care workers were experiencing stress, 86% reported experiencing anxiety, 77% reported frustration, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 75% said they were overwhelmed.[9]

The pandemic has also impacted public health workers employed at state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments. A survey of these workers during March 29–April 16, 2021 revealed that 53% of respondents reported symptoms of at least one adverse mental health condition in the preceding two weeks. The most prevalent conditions were depression (32%), anxiety (30%), post-traumatic stress disorder (37%), and suicidal ideation (8%).[10] Most respondents worked directly on COVID-19 response activities.

Suicide Prevention within the Healthcare Workforce

Given the amount of time people spend at work in a lifetime, workplaces can play a key role in protecting and promoting mental health and well-being and helping to prevent suicide. This is particularly relevant since suicide is the second leading cause of death among people ages 10-34 and the fourth leading cause among those ages 35-54 – people of working age.[2] Action can be taken in many workplaces to prevent suicide and support positive mental health.

Primary prevention efforts in the workplace seek to reduce the risk of suicide by preventing work stress and difficult working conditions. Employers can take a holistic approach to making changes at work that can affect overall health and well-being, including physical, psychological, social, and economic aspects. This can include:

- keeping workers safe,

- paying attention to hours and demands with appropriate work schedules, adequate time off and staffing, as well as appropriate quantity and intensity of work,

- promoting a positive workplace culture,

- ensuring worker respect,

- supporting work-life fit, and

- preventing negative factors such as discrimination and bullying.

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention has a Comprehensive Blueprint for Workplace Suicide Prevention that provides guidance to workplaces to promote mental health and suicide prevention. This comprehensive blueprint includes screening, mental health services and resources, suicide prevention training, life skills and social network promotion, crisis management, policy and means restriction, education and advocacy, social marketing, and guidance for leadership.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices provides strategies with the best available evidence to prevent suicide. These strategies address preventing suicide risk before it occurs as well as prevention that seeks to keep people safe who may already be at risk. These two categories of strategies can be supported and implemented by employers. Prevention strategies that employers can consider include:

- Increasing access to mental health screening tools for self-assessment

- Increasing access to behavioral health care services (e.g., Employee Assistance Programs) and offering easy access for employees to helping services (e.g., mental health and substance use disorder treatment, financial counseling)

- Promoting connectedness and a sense of community

- Improving organizational policies to create safer workplaces, including strategies to reduce access to lethal means of suicide within workplaces

- Identifying and supporting people at risk through gatekeeper training for managers’ and supervisors, where gatekeepers are those who are identified as having the potential to observe changes in mood and behaviors of others[11]

- Helping to educate colleagues at all levels about the role they play in keeping themselves and their colleagues safe and well

- Encouraging colleagues to have caring conversations and take action to be there for others, especially those who are struggling

- Teaching coping and problem-solving skills, including relationship and parenting programs

- Offering support and preventing future risk after death of a co-worker by suicide

We Want to Hear from You

If you are an employer in the health sector, how is your organization taking action to support the mental health of its workers and prevent suicide? What challenges have you faced in supporting your workers’ mental health? Please share your answers in the comments below.

Resources

- Suicide and Occupation

- Healthcare Workers: Work Stress & Mental Health

- Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices

- Comprehensive Blueprint for Workplace Suicide Prevention

- Framework for Successful Messaging

- COVID-19 Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Key Messages

- Healthcare Personnel and First Responders: How to Cope with Stress and Build Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Vital Signs

Hope Tiesman, PhD, is a research epidemiologist in the NIOSH Division of Safety Research

David Weissman, MD, is the director of the NIOSH Respiratory Health Division

Deborah Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, is the lead behavioral scientist on the Suicide Prevention Team in CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

Kristen Quinlan, PhD, is a research scientist at the Education Development Center and data measurement advisor at the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

L. Casey Chosewood, MD, MPH, is the director of the NIOSH Office for Total Worker Health®

References

1. NCIPC [2021]. Suicide Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Website accessed on 09/08/2021. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/index.html

2. NCIPC [2018]. 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, U.S. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2018_1100w850h.jpg.

3. Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD [2013]. Suicide by occupation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 203(6):409-416.

4. Milner A, Witt K, LaMontagne AD, Niedhammer I [2018]. Psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Occup Environ Med 75(4):245-253.

5. Choi BK [2018]. Job strain, long work hours, and suicidal ideation in US workers: A longitudinal study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 91(7):865-875.

6. Milner A, Witt K, Maheen H, LaMontagne AD [2017]. Access to means of suicide, occupation and the risk of suicide: A national study over 12 years of coronial data. BMC Psychiatry 17:125

7. Milner A, Page K, Spencer-Thomas S, LaMontagne AD [2015]. Workplace suicide prevention: a systematic review of published and unpublished activities. Health Promot Int 30(1):29-37.

8. Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, Dambrun M, Moustafa F, Mermillod M, et al. (2019) Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14(12): e0226361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.

9. The Mental Health of Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 | Mental Health America (mhanational.org)

10. Bryant-Genevier J, Rao CY, Lopes-Cardozo B, et al. Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and Suicidal Ideation Among State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, March–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:947–952. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7026e1

11. Mortali M.G., Moutier C. (2019) Suicide Prevention in the Workplace. In: Riba M., Parikh S., Greden J. (eds) Mental Health in the Workplace. Integrating Psychiatry and Primary Care. Springer, Cham.

Posted on by