Bringing Strategic Foresight to OSH

Posted on byHow do we effectively plan for the future of occupational safety and health (OSH) when numerous social, technological, economic, environmental, and political trends are influencing work, the workplace, and the workforce? The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and others in the OSH field are working to ensure we are ready to address the challenges of the future when they arrive.

A new paper in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health proposes integrating strategic foresight into OSH research and practice. This future-oriented way of thinking and planning can help OSH professionals more actively anticipate, and even shape, the systems influencing the future of worker safety, health, and well-being. Equal parts science and art, strategic foresight includes the development and analysis of plausible alternative futures as inputs to strategic plans and actions. The article reviews several published foresight approaches and examples of work-related futures scenarios. It also presents a working foresight framework tailored for OSH and offers recommendations for next steps to incorporate strategic foresight into research and practice to advance worker safety, health, and well-being. This blog defines strategic foresight and introduces the foresight framework tailored for OSH.

Strategic Foresight Defined

Strategic foresight is a practice rooted in futures studies designed to help better understand, prepare for, and influence the future.[1] Strategic foresight recognizes the future is not predetermined or predictable.[2] Instead, the roots of multiple plausible futures exist today in the form of weak or early signals of potential change.[3] Identifying and monitoring these signals can reduce the likelihood of being unprepared for or surprised by emerging trends and changes as they arrive in the mainstream. It can also uncover points at which today’s decisions and actions can be leveraged to move toward desirable futures.

Strategic foresight is a complement to, and not a substitute for, strategic planning. Traditional strategic planning reviews evidence from the past and asks how we might do things better, faster, or more proficiently in the future. Conversely, strategic foresight looks ahead and asks what may be coming, how it might affect us, and what we can do today to start moving toward a preferred outcome.

Engaging in strategic foresight involves the completion of two distinct, yet interrelated, tasks. The first task includes mapping futures, which consists of developing functional views of alternative futures. [4] ,[5], [6] The second task includes assessing the implications and critical issues associated with the alternative functional futures to inform the design and implementation of feasible and responsive strategic options.[3] A number of different foresight models and frameworks exist. Several of the most popular approaches cited in the published literature are discussed in the journal article.

Many of the popular foresight models and frameworks are designed to produce scenarios, which are stories describing plausible alternative futures. Because the future is not predetermined or predictable, multiple scenarios are created for a single foresight project. This multi-scenario approach has long been utilized as part of business, military, public policy, and emergency preparedness strategic planning efforts.[7], [8],[9],[10] The practice originated in the 1950s, when the RAND Corporation first began using scenario techniques to develop U.S. military strategies.[11] Royal Dutch Shell was an early adopter of scenario planning in the business world. Their use of scenario planning as a business strategy helped them prepare for and gain competitive advantage during major adverse events in the oil industry, such as the 1973 oil crisis and the 1980s oil bust.[12] Today, many major organizations across a variety of industries incorporate scenario planning into their business culture, which has allowed them to remain resilient through—and even thrive on—the changes and challenges they have faced over time.[13]

Foresight Framework for OSH

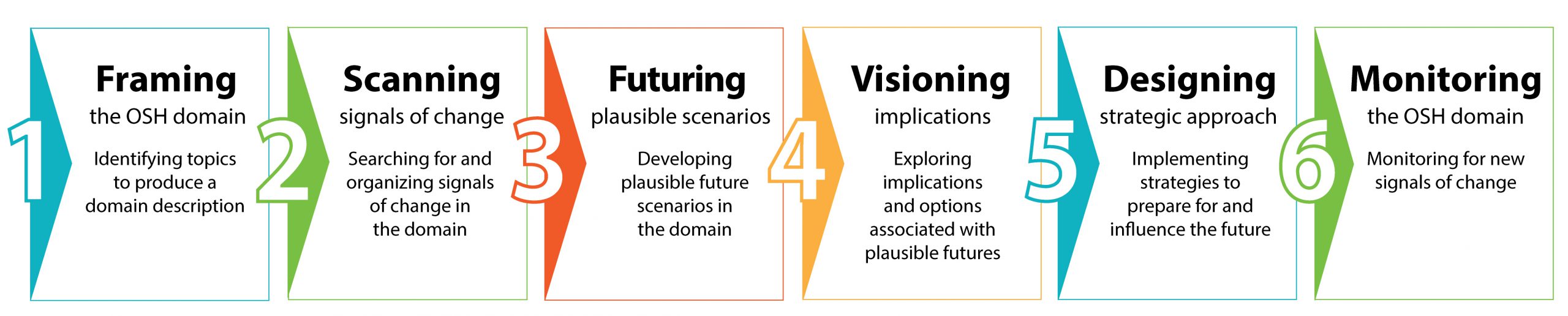

The concept of applying strategic foresight to explore work-related futures is not entirely new, but so far has been underutilized in OSH. To further the application of strategic foresight in OSH, NIOSH has adapted the widely used University of Houston Framework Foresight.[5],[14],[15] NIOSH elected to build on Framework Foresight because it is an internationally renowned approach that is versatile and flexible enough to accommodate a variety of project topics and aims while also providing a clear, step-by-step roadmap through the foresight process. The intent of this NIOSH Foresight Framework for OSH, presented in Figure 1, is to help bridge the current OSH-foresight gap and bring foresight into OSH conversations and planning practices.

Figure 1. Foresight Framework for Occupational Safety and Health (OSH). Adapted from the UH Foresight Framework

Like the University of Houston Framework Foresight, the NIOSH Foresight Framework for OSH has six discrete stages that are interrelated and interdependent:

- Framing: identifying and describing the domain or topic of interest, the central question or issue to be explored, the ‘client’ or intended audience, the geographic scope of the effort, and the time horizons the project will consider.

- Scanning: searching a variety of sources for information about how things might be different in the future.

- Futuring: developing alternative future scenarios using techniques that meet the needs of the identified client.

- Visioning: considering the implications of the different scenarios for the client, which can uncover potential risks, challenges, and opportunities associated with each scenario and identify the client’s degree of preparedness for implementing the changes needed to create and sustain the client’s preferred future.

- Designing: planning and constructing strategic approaches that can guide the client’s actions today in support of the desired future.

- Monitoring: continuing to scan for new signals of change and updating the domain topic as needed to further refine future foresight efforts.

Though the framework is presented as a sequential model, the strategic foresight process is not entirely linear. Both during and at the end of each stage within the framework, users are encouraged to reflect upon the activities they have completed in previous stages and determine if any additional work is needed before moving on the to the next stage. Engagement with and integration of relevant stakeholders is also encouraged throughout the entire foresight process and should be tailored at each stage to effectively support the project purpose.

NIOSH is currently testing and evaluating the framework with a foresight pilot project exploring “the future of OSH” as a priority domain. The project team plans to report the process and results of the effort in a future peer-reviewed publication.

Next Steps

To ensure strategic foresight has staying power in the OSH community, it will be imperative to invest time and resources into building strategic foresight capacity. Enhancing OSH awareness and knowledge of strategic foresight will be key. See the resources below to learn more about internationally recognized foresight organizations and offerings in the United States and Europe. In addition, the Federal Foresight Community of Interest, an interagency organization providing a forum for federal agencies in the United States interested in applying foresight, is well-positioned to provide OSH with insights on best practices and strategies for building and sustaining a connected foresight community.

The future may be largely unpredictable, but it does not have to be a complete surprise when it arrives. The OSH community cannot sufficiently identify and prepare for the potential future risks and hazards that may influence worker safety, health, and well-being using only conventional strategic planning. Complementary forward-looking methods are also needed to help us design and refine proactive risk management programs and strategies. Strategic foresight in OSH may help inform the development of proactive systems to prevent injury, illness, death, and disability and promote worker well-being across the working life continuum for generations of future workers.

This blog offers a brief introduction to strategic foresight and discusses the NIOSH Foresight Framework. If we piqued your curiosity, please read the full article for much more detail. If you have used strategic foresight in OSH or other fields, we would like to hear about your experiences.

Jessica MK Streit, PhD, CHES® , is the Deputy Director of the NIOSH Office of Research Integration

Sarah A Felknor, MS, DrPH, is the Associate Director for Research Integration at NIOSH

Nicole T Edwards, MS, is a Program and Information Specialist at NIOSH

John Howard, MD, is the Director of NIOSH

Resources

- Association of Governmental Risk Pools (AGRiP). Framing the Future: A Guide to Strategic Foresight

- Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies. Applied Strategic Foresight

- Federal Foresight Community of Interest (FFCOI)

- Institute for the Future (IFTF). Forecasts + Perspectives

- Institute for Futures Research. NEDLAC Futures of Work in South Africa

- International Labour Organization; ITC Limited Foresight Toolkit. Three Horizons Framework

- Policy Horizons Canada. Foresight Training Modules

- University of Houston. Professional Certificate in Foresight

- United Nations Development Programme. Foresight Manual: Empowered Futures for the 2030 Agenda

- University of Oxford. Oxford Scenarios Programme

References

[i] Iden, J.; Methlie, L.; Christensen, G. The nature of strategic foresight research: A systematic literature review. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 116, 87–97, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.002.

[ii] Voros, J. A Primer on Futures Studies, Foresight, and the Use of Scenarios. Foresight Bull. 2001, 6, 1–8. Available online: https://foresightinternational.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Voros-Primer-on-FS-2001-Final.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

[iii] Bishop, P.; Hines, A. Teaching about the Future; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

[iv] Hines, A. Strategic foresight: The state of the art. Futurist 2006, 40, 18–21.

[v] Hines, A.; Bishop, P. Thinking about the Future: Guidelines for Strategic Foresight, 2nd ed.; Hinesight: Houston, TX, USA, 2015.

[vi] Institute for the Future (IFTF). Forecasts + Perspectives. Available online: https://www.iftf.org/what-we-do/forecasts/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

[vii] Schoemaker, P. Scenario planning—A tool for strategic thinking. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1995, 36, 25–40.

[viii] Bradfield, R.; Wright, G.; Burt, G.; Cairns, G.; Van Der Heijden, K. The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures 2005, 37, 795–812, doi:0.1016/j.futures.2005.01.003.

[ix] Rhisiart, M.; Miller, R.; Brooks, S. Learning to use the future: Developing foresight capabilities through scenario processes. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 101, 124–133, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.015.

[x] Rohrbeck, R.; Battistella, C.; Huizingh, E. Corporate foresight: An emerging field with a rich tradition. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 101, 1–9, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.002.

[xi] Schoemaker, P. Multiple scenario development: Its conceptual and behavioral foundation. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 193–213.

[xii] Wack, P. Scenarios: Unchartered waters ahead. Bus. Rev. 1985, 63, 72–89.

[xiii] Schwartz, P. The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World; Currency Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1996.

[xiv] Hines, A.; Bishop, P. Framework foresight: Exploring futures the Houston way. Futures 2013, 51, 31–49, doi:10.1016/j.futures.2013.05.002.

[xv] Hines, A. Strategic Foresight. Training seminar presented to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; Online presentation, Sept 14-18, 2020.

Posted on by