Take Action Now to Prevent Heat-Related Illness at Work

Posted on by

Before we enter summer, we should plan ahead for work-related heat exposure and the potential for heat-related illness among workers. Exposure to heat combined with physical activity and other factors in the environment can increase the body’s temperature and cause heat stress. The body responds to heat stress by trying to stabilize body temperature, a process which can lead to heat strain. Many factors impact work-related heat stress and heat strain, including air temperature, humidity, clothing, personal protective equipment, and hydration. Heat stress that leads to unrelieved heat strain increases the risk for heat-related illness. Prevention of heat-related illness in workers may be needed year-round, depending on work duties and the environment.

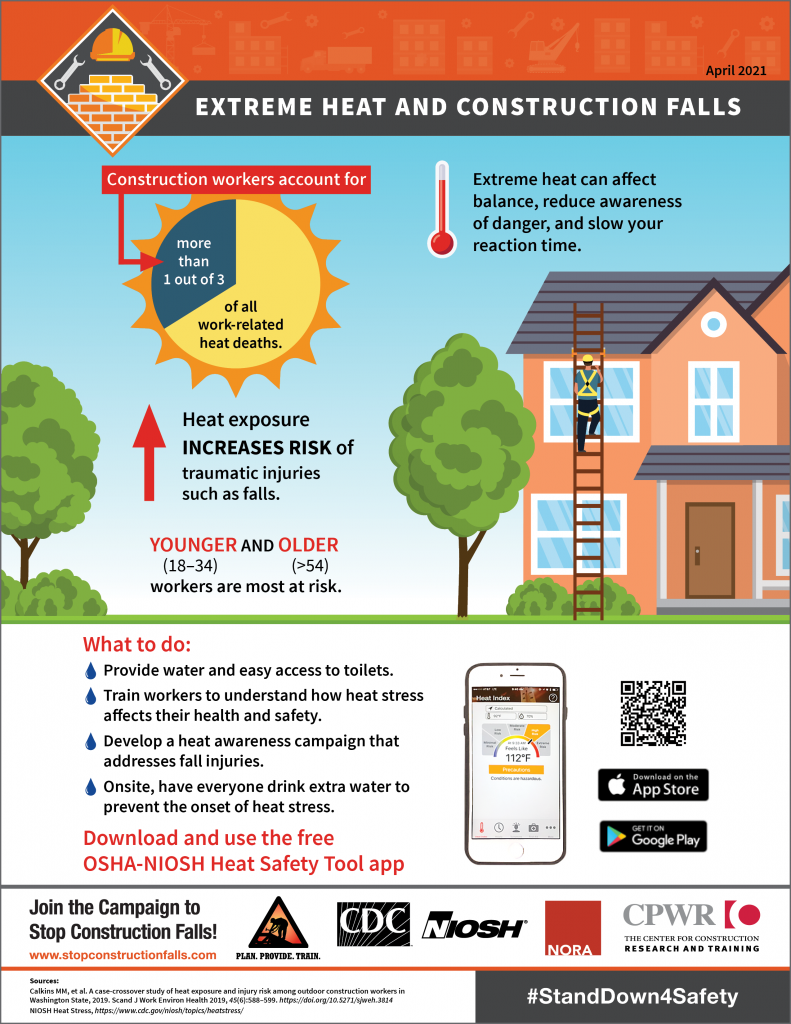

Heat stress and heat strain can also increase the risk of other types of workplace injuries.[1],[2] For example, workers experiencing heat stress or strain have an increased risk of injuries from dizziness or falls. See infographic at right.

Heat Stress Impacts Many Types of Workers

Workers in a wide variety of industries are exposed to hot environments during work and are at risk for heat-related illness. A recent study using California state-wide workers’ compensation data identified public administration (35% of the total cases); agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (13%); and construction (8%) as industry groups with the highest number of heat-related illnesses. Industries with the highest rates were agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting; public administration; and mining.[3] Younger workers and male workers were at greater risk than other demographic groups. This study also found that 9% of heat-related illness cases happened to new workers within two weeks of hire.

Heat Stress at Work and Kidney Injury: An Emerging Issue

Emerging issues associated with occupational heat stress are acute kidney injury, the sudden loss of kidney function, and chronic kidney disease (the slow and gradual loss of kidney function). Kidney failure can lead to a range of illnesses and even death. The risk of acute kidney injury increases with high body temperatures and lack of water during physical work in the heat.[4] Researchers studying chronic kidney disease of nontraditional origin identified occupational heat stress as the strongest risk factor.[5]

A serious condition involving the kidneys is rhabdomyolysis, which is caused by high body temperature, physical exertion, overuse of muscles, and/or damage to muscles (e.g., crush injury from a fall). With rhabdomyolysis, damaged muscle breaks down and releases excess proteins and electrolytes into the blood, causing kidney damage and other severe medical problems.

Many occupations present an increased risk for workers for heat‐related acute and chronic kidney injury at work; for example, one study found that large numbers of mail and package delivery workers experience acute kidney injury.[6] A recent science review of chronic kidney injury prevention among agricultural workers suggested that addressing several workplace factors including hyperthermia, hydration, and other factors at once is necessary.[7]

Plan Ahead: Address Workplace Heat Before Exposing Workers

Many workplace controls are available to minimize heat-related illness among workers. A complete heat stress program for the workplace should include assessing the risk, limiting heat exposure, reducing metabolic heat load, acclimating workers, encouraging hydration, and providing periodic training for heat stress and heat-related illness. Workplace-based educational programs have been shown to improve workers’ knowledge about heat illness;[8] training has been identified as a central part of a heat stress educational program to decrease heat-related illness among outdoor workers.[9]

When providing heat stress education and training, consider your workers and what delivery methods might work best. Small construction firms may face language and communication challenges when providing training to immigrant workers.[10] Small businesses often have fewer resources, greater time demands on managers, and fewer employees to address safety.[11] [12] [13] [14] As a result, small businesses are burdened with higher injury and fatality rates.[15] [16]

For many immigrant workers, a combination of factors can make them more vulnerable to heat-related illnesses, including seasonality, extreme work conditions, a lack of knowledge and safety training, poverty, cultural differences, and language barriers.[17] [18] [19] [20] [21] Delivery methods for education and training should consider length of time for trainings (for example, short trainings spaced out over a few days if a longer training does not fit work schedules) and formats of handouts and other shared educational materials (for example, concise, illustrated and available in multiple languages). The NIOSH Heat Stress topic page has a variety of materials, including guidance, posters, fact cards, infosheets, and a mobile app that may be used to supplement trainings. Train workers before hot outdoor work begins and tailor training to cover worksite-specific conditions.

NIOSH Recommended Heat Stress Training Program Elements

Employers should provide heat stress training for all workers and supervisors on the following:

• Recognizing the signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses and administration of first aid.

• Causes of heat-related illnesses and the procedures that will minimize the risk, such as drinking enough water and monitoring the color and amount of urine output.

• Proper care and use of heat-protective clothing and equipment and the added heat load caused by exertion, clothing, and personal protective equipment.

• Effects of non-work factors (such as drugs, alcohol, obesity, etc.) on ability to adapt to occupational heat stress.

• The importance of acclimatization (see below).

• The importance of immediately reporting to the supervisor any symptoms or signs of heat-related illness in themselves or in coworkers.

• Procedures for responding to symptoms of possible heat-related illness and for contacting emergency medical services.

In addition, supervisors should also be trained on:

• How to implement appropriate acclimatization.

• Procedures to follow when a worker has symptoms consistent with heat-related illness, including emergency response procedures.

• Monitoring weather reports and responding to hot weather advisories.

• Monitoring and encouraging adequate fluid intake and rest breaks.

Acclimatize Your Workforce

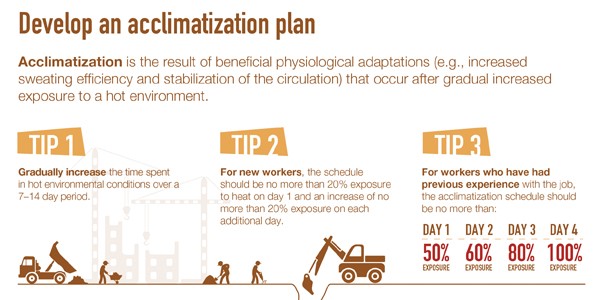

Over time, our bodies can often be trained to better tolerate heat exposure through a gradual process known as acclimatization. Heat strain occurs as the body attempts to maintain a safe and stable body temperature. Excessive heat strain can by identified by profuse sweating, rapid heart rate and elevated core body temperature. During acclimatization, the body becomes more efficient at maintaining a safe and stable core temperature.

Lack of work experience and acclimatization are well‐established risk factors for heat-related illness.[22] A 2018 case series of heat-related illnesses found that nearly 75% of fatal incidents occurred in the first week on the job.[23] Workers can become acclimatized to heat by steadily increasing their work time in hot environments over several days. Despite the evidence for needing acclimatization, a 2018 study of cleanup responders found that only about 1 in 4 reported using an acclimatization plan.[24]

Strategies for acclimatizing workers include gradually increasing workers’ time in hot conditions over 7 to 14 days; and planning for a range of schedules for new or returning workers to increase their exposure. Training for supervisors should include how to appropriately acclimatize and supervise new employees the first 14 days or until they are fully acclimatized.

Resources

The following resources will help you develop and implement a program to address hot working conditions and prevent heat-related illness.

- NIOSH Heat Stress

- NIOSH Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments

- NIOSH Heat Stress: Acclimatization Fact Sheet

- NIOSH Rhabdomyolysis

- NIOSH Science Blog: Heat Stress Imposed by PPE Worn in Hot and Humid Environments

- NIOSH Science Blog: Heat Stress in Construction

- NIOSH Science Blog: Adjusting to Work in the Heat: Why acclimatization Matters

- OSHA Safety and Health Topics: Heat

- OSHA Water. Rest. Shade. – Acclimatizing Workers

- CPWR Working in Hot Weather

We would love to hear from you

In the comment section below, please share your workplace heat stress prevention successes and challenges that you’ve faced.

- Has your workplace developed innovative or unique training materials or methods you feel may be helpful to others?

- What are the primary challenges your workplace faces in incorporating acclimatization as part of your overall workplace OSH plan related to excessive heat?

Douglas Trout, MD, MHS, is a medical officer at NIOSH.

Brenda Jacklitsch, PhD, MS, is Coordinator of the NIOSH Small Business Assistance Program and a research health scientist in the Division of Science Integration.

Scott Earnest, PhD, PE, CSP, is the Associate Director for Construction Safety and Health.

CDR Elizabeth Garza, MPH, CPH, is Assistant Coordinator for the Construction Sector in the NIOSH Office of Construction Safety and Health.

J’ette Novakovich, PhD, MS, is Assistant Coordinator of the Emergency Preparedness and Response, Core and Specialty Program and a Writer-Editor in the Division of Science Integration.

This blog has been translated into Spanish.

References

[1] Varghese BM, Hansen AL, Williams S, Bi P, Hanson-Easey S, Barnett AG, et al [2018]. Are workers at risk of occupational injuries due to heat exposure? A comprehensive literature review. Safety Science 110: 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.04.027

[2] Calkins MM, Bonauto D, Hajat A, Lieblich M, Seixas N, Sheppard L, Spector JT [2019]. A case-crossover study of heat exposure and injury risk among outdoor construction workers in Washington State, 2019. Scand J Work Environ Health 45(6):588–599. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3814

[3] Heinzerling A, Laws RL, Frederick M, Jackson R, Windham G, Materna B, Harrison R [2020]. Risk factors for occupational heat‐related illness among California workers, 2000–2017. Am J Ind Med 63:1145–1154. DOI: 10.1002/ajim.23191

[4] Chapman CL, Johnson BD, Vargas NT, Hostler D, Parker MD, Schlader ZJ [2020]. Both hyperthermia and dehydration during physical work in the heat contribute to the risk of acute kidney injury. J Appl Physiol 128: 715–728.

[5] Wesseling C, Glaser J, Rodríguez-Guzmán J, Weiss I, Lucas R, Peraza S, et al [2020]. Chronic kidney disease of non-traditional origin in Mesoamerica: a disease primarily driven by occupational heat stress. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e15. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.15

[6] Tannis C [2020]. Letter to the editor: Heat illness and renal injury in mail and package delivery workers. Am J Ind Med 63:1059–1061. DOI: 10.1002/ajim.23169

[7] Hansson E, Glaser J, Jakobsson K, Weiss I, Wesseling C, Lucas RAI, et al [2020]. Pathophysiological mechanisms by which heat stress potentially induces kidney inflammation and chronic kidney disease in sugarcane workers. Nutrients 12: 1639. doi:10.3390/nu12061639

[8] El-Shafei DA, Bolbol SA, Awad Allah MB, Abdelsalam AE [2018]. Exertional heat illness: knowledge and behavior among construction Workers. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:32269–32276

[9] McCarthy RB, Shofer F, Green-McKenzie J [2018]. Occupational heat illness in outdoor workers before and after the implementation of a heat stress awareness program. https://oem.bmj.com/content/75/Suppl_2/A505.1

[10] Cunningham TR, Guerin RJ, Keller BM, Flynn MA, Salgado C, Hudson D [2018]. Differences in safety training among smaller and larger construction firms with non-native workers: Evidence of overlapping vulnerabilities. Safety Science 103:62-69.

[11] De Kok JM [2005]. Precautionary actions within small and medium‐sized enterprises. J Journal of Small Business Management 43(4):498-516.

[12] Hasle P and Limborg HJ [2006]. A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Ind Health 44(1):6-12.

[13] Parker D, Brosseau L, Samant Y, Pan W, Xi M, Haugan D [2007]. A comparison of the perceptions and beliefs of workers and owners with regard to workplace safety in small metal fabrication businesses. Am J Ind Med. 50(12):999-1009.

[14] Sinclair RC and Cunningham TR [2014]. Safety activities in small businesses. Safety Science 64:32-38.

[15] Buckley JP, Sestito JP, Hunting KL [2008]. Fatalities in the landscape and horticultural services industry, 1992–2001. Am J Ind Med. 51(9):701-713.

[16] Mendeloff JM, Nelson C, Ko K, Haviland A [2006]. Small businesses and workplace fatality risk: an exploratory analysis. Vol. 371. Rand Corporation.

[17] Gany F, Dobslaw F, Ramirez J, Tonda J, Lobach I, and Leng J [2011]. Mexican urban occupational health in the US: A population at risk. Journal of community health 36(2):175-179.

[18] Gomberg‐Muñoz R [2010]. Willing to work: Agency and vulnerability in an undocumented immigrant network. J American Anthropologist 112(2):295-307.

[19] Flynn MA [2014]. Safety & the diverse workforce: lessons from NIOSH’s work with Latino immigrants. Professional Safety 59(6):p. 52.

[20] Brunette M [2005]. Development of educational and training materials on safety and health: Targeting Hispanic workers in the construction industry. J Family Community Health. 28(3):253-266.

[21] Stoecklin-Marois M, Hennessy-Burt T, Mitchell D, Schenker M. [2013]. Heat-related illness knowledge and practices among California hired farm workers in The MICASA Study. Ind Health 51(1): p. 47-55.

[22] Arbury S, Jacklitsch B, Farquah O, Hodgson M, Lamson G, Martin H, Profitt A; Office of Occupational Health Nursing, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) [2014]. Heat illness and death among workers – United States, 2012-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 63(31):661-665.

[23] Tustin AW, Cannon DL, Arbury SB, Thomas RJ, Hodgson MJ [2018]. Risk factors for heat-related illness in U.S. workers: an OSHA case series. JOEM 60 (8). DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001365

[24] Jacklitsch BL, King KA, Vidourek RA, Merianos AL [2018]. Heat-Related Training and Educational Material Needs among Oil Spill Cleanup Responders, Environmental Health Insights, 12: 1178630218802295. DOI: 10.1177/1178630218802295

Posted on by