Hearing Loss Among Construction Workers: Chemicals Can Make It Worse

Posted on by

Three out of four construction workers are exposed to hazardous noise levels on the jobsite.[i] Noise levels are considered hazardous when they reach 85 decibels or higher. A NIOSH study examining hearing loss across industries found that construction workers have higher levels of hearing loss than workers in most industries.[ii] The highest rates are experienced by construction workers in nonresidential building construction, highway and bridge construction, and heavy and civil engineering. [iii] With power tools, mobile equipment, and other sources of hazardous noise present at many construction sites, workers have multiple reasons to wear hearing protection devices. Even so, one study found that one out of three construction workers exposed to hazardous noise did not wear hearing protection.[iii]

A lesser known threat to hearing loss that is present at nearly every construction site across the country and that can cause just as much, if not more damage to hearing than loud noises, are chemicals.

Hazardous Chemicals Can Cause Hearing Loss

Hazardous chemicals are not only dangerous to our health from inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact, but they can also cause hearing loss when combined with sound levels that are lower than the NIOSH recommended 85 decibel time weighted average exposure limit for noise.

Many chemicals can enhance the damaging effects of noise when individuals are exposed to both loud sounds and chemicals. This type of hearing loss is known as ototoxicity. Ototoxicity occurs when chemical substances affect the auditory or hearing system. Many workers are unaware that hearing loss has occurred until completing an audiogram and reviewing the results with a physician or other licensed healthcare provider.

Hundreds of ototoxicant chemicals have been identified by NIOSH and others:[iv] [v] [vi]

Hundreds of ototoxicant chemicals have been identified by NIOSH and others:[iv] [v] [vi]

- Pharmaceuticals (such as aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and loop diuretics)

- Solvents (such as toluene, xylene, and styrene, found in thinners, degreasers and many paints)

- Asphyxiants (such as carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and tobacco smoke)

- Nitriles (such as butenenitrile, cis-2-pentenenitrile, and acrylonitrile)

- Metals and Compounds (such as mercury compounds, organic tin compounds, and lead)

- Pesticides (such as organophosphates, paraquat, pyrethroids, hexachlorobenzene)

Protecting Workers from Chemicals That Can Cause Hearing Loss

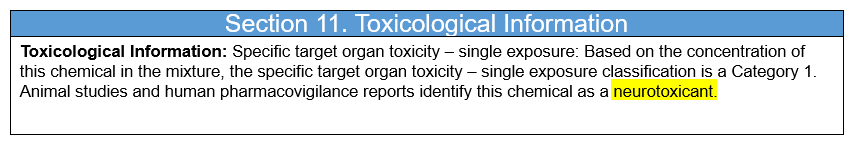

To prevent hearing loss, chemicals that have ototoxic characteristics should be identified prior to exposure. Workers and employers should review chemical safety data sheets (SDSs) to identify the various ototoxic chemicals currently used in the workplace. Below is the toxicological section of a sample SDS that shows where a chemical is identified as a potential neurotoxicant (ototoxicants are often called neurotoxicants). If that is the case, check the symptoms associated with exposure to see if they include hearing complaints.

In 2019, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) adopted an ototoxicant [OTO] notation to highlight a chemical’s ability to cause hearing loss either alone or in combination with noise.[vii] If ototoxicant chemicals are present, the ACGIH suggests noise exposure reduction using engineering, administrative, and PPE controls. They also suggest placing affected employees in hearing conservation and medical surveillance programs to monitor hearing loss.

Specifically, when workers are exposed to noise and ototoxicants such as carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, lead, and solvent mixtures, ACGIH suggests that employers should conduct periodic audiograms. Audiograms should also be provided in the absence of noise when ethylbenzene, styrene, toluene, or xylene exposures are present in the workplace.

Eliminate or Substitute Ototoxic Chemicals When Possible

Consider the risks associated with ototoxic chemicals and determine if they are vital to the job site and the desired outcomes of the project. By performing a risk-assessment, organizations can evaluate the harmful effects of chemicals on their jobsites, and make an informed decision as to whether or not a safer alternative should be used. In addition, organization’s procurement departments and related personnel should be trained to identify chemicals that are potential ototoxicants so that the hazard can be identified before the hazardous product is purchased.

Can the work process be revised to eliminate the ototoxic chemical or substitute the chemical being used for one that is less hazardous? For example, if an electric portable generator can achieve the same results as a comparable gasoline-powered version, this could be a simple way to reduce your workers’ exposure to carbon monoxide from the generator’s exhaust, as well as the toluene that is found in the gasoline; both of these agents are ototoxicants.[viii] If this is not feasible, consider implementing engineering and/or administrative controls, such as reducing the number of exposed workers or reducing the duration of exposure.

Proper Hearing Conservation Involves All Levels of an Organization

When employers are considering ways to prevent work-related hearing loss, the decision-making process should involve input from all levels of the organization. An organization must have leadership support in order to stop hearing loss within the construction industry, as well as obtaining buy-in from the frontline employees. By engaging with departments at all levels of the organization to achieve a common goal, it not only promotes hazard recognition and employee engagement, but it helps create a stronger hearing loss prevention program.

Preventing exposure to ototoxicant chemicals is an important step in reducing hearing loss in the construction industry. During National Protect Your Hearing Month make it a point to examine the chemical safety data sheets at your construction site to see if ototoxicants are in use.

For more information on risk factors for hearing loss, please visit the NIOSH Noise and Hearing Loss Prevention topic page and the blog Ototoxicant Chemicals and Workplace Hearing Loss.

Drew Hinton, MS, CSP, CHMM, COHC, is a Contractor for the NIOSH Office of Construction Safety and Health.

CDR Elizabeth Garza, MPH, CPH, is Assistant Coordinator for the Construction Sector in the NIOSH Office of Construction Safety and Health.

Jeanette Novakovich, MA, MS, PhD, is Assistant Coordinator for Emergency Preparedness Response Program in the NIOSH Office of Emergency Response Preparedness and Response Office and Writer-Editor in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Scott Earnest, PhD, PE, CSP, is the Associate Director for Construction Safety and Health.

Thais Morata, PhD, is a Research Audiologist in the NIOSH Division of Field Studies and Engineering.

Trudi McCleery, MPH, is a Health Communications Specialist in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration, Science Applications Branch.

References

[i] CPWR (2010). The construction chart book: ONET database and occupational exposures in construction. CPWR-The Center for Construction Research and Training. Silver Spring, MD

[ii] Masterson, E.A., Tak, S., Themann, C.L., Wall, D.K., Groenewold, M.R., Deddens, J.A. and Calvert, G.M. (2013), Prevalence of hearing loss in the United States by industry. Am. J. Ind. Med., 56: 670-681. doi:10.1002/ajim.22082

[iii] Tak, S., R. R. Davis and G. M. Calvert (2009). “Exposure to hazardous workplace noise and use of hearing protection devices among US workers–NHANES, 1999-2004.” Am J Ind Med 52(5): 358-371.

[iv] Nordic Expert Group (2010). 142. Occupational exposure to chemicals and hearing impairment. Johnson AC, Morata TC. The Nordic Expert Group for Criteria Documentation of Health Risks from Chemicals. Nordic Expert Group. Gothenburg. Arbete och Hälsa; 44(4): 177 pp. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/23240

[v] Occupational Safety and Health Administration and National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (2018). Preventing Hearing Loss Caused by Chemical (Ototoxicity) and Noise Exposure. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2018-124/default.html

[vi] NIOSH (1996). Preventing Occupational Hearing Loss – A Practical Guide. Human Health Services, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute of Occupational Safety: Washington DC. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Number 96-110. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/96-110/default.html

[vii] American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists [ACGIH]. Threshold limit values and biological exposure indices. Cincinnati, OH: ACGIH 2019.

[viii] Pillion J. P. (2012). Sensorineural Hearing Loss following Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. Case reports in pediatrics, 2012, 231230. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/231230

Posted on by