Wholesale Recycling: High Rates of Injuries and Illnesses

Posted on by

The U.S. wholesale recycling material industry consists of about 12,700 wholesale companies, providing an estimated 102,038 jobs [Siccode.com 2020]. Unlike recycling services that pick up empty cartons, cans, and bottles curbside from households, wholesale recycling merchants buy automotive scrap, electronic scrap, industrial scrap, or other recycling materials from manufacturers and resell it to businesses, government agencies, other wholesalers, or retailers. Tasks in these facilities include receiving, sorting, shredding, disassembly, refurbishing, and shipping. Wholesale recycling facilities are among the most dangerous workplaces.

A recent publication featured on the NIOSH Science Blog reviewed the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) wholesale and retail trade fatal and nonfatal injury and illness data from 2006–2016. The study reported that in 2016 the fatality rate experienced among workers in the recyclable material merchant wholesale subsector was nearly seven times higher than the rate experienced by workers in private industry overall [Anderson et al. 2020].

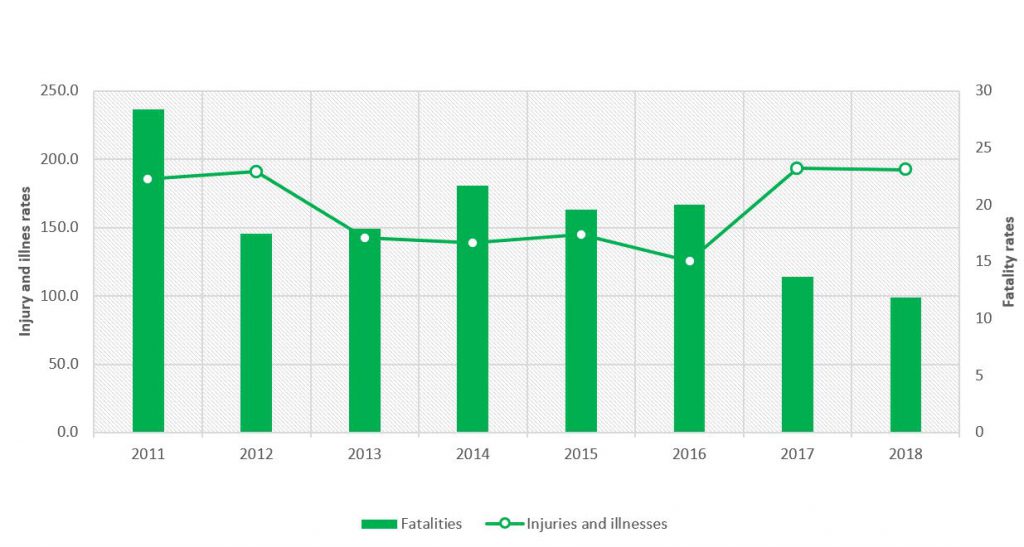

Fatality rates in this subsector were at their highest mark in 2011, and since have mostly fallen [BLS 2020a]. Until recently, injuries and illness rates were also falling. In 2017, a large increase in injury and illness rates took place, an increase which stabilized the following year [BLS 2011–2018]. See Figure 1.

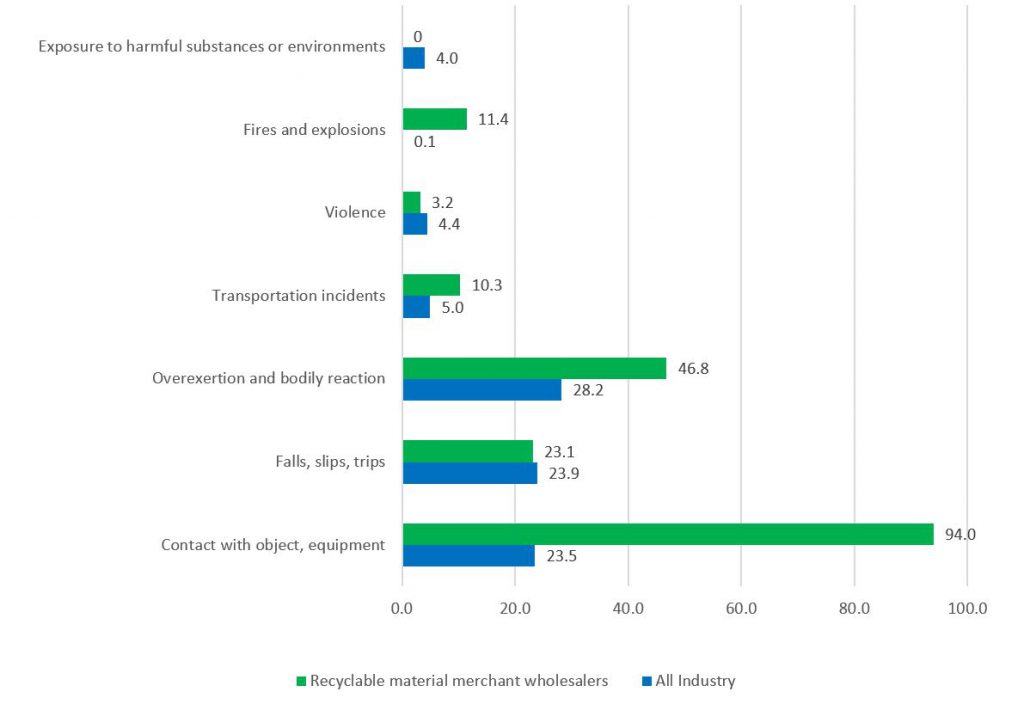

Contact with objects or equipment in the recycling wholesale subsector is a leading cause for injury and a serious concern. This type of injury among wholesale recycling workers is 4 times higher than the rates experienced by private industry workers overall [BLS 2020b]. See Figure 2 below. Anderson et al. [2020] reported that demographic factors may have safety and health significance. Industry sectors with a high proportion of male workers have been found to have higher injury rates, particularly associated with contact with object injuries [Coate 2019]. The wholesale recycling subsector workforce is 81% male [BLS 2020c], a proportion higher than reported in the overall wholesale sector (71% male) [Anderson et al. 2020].

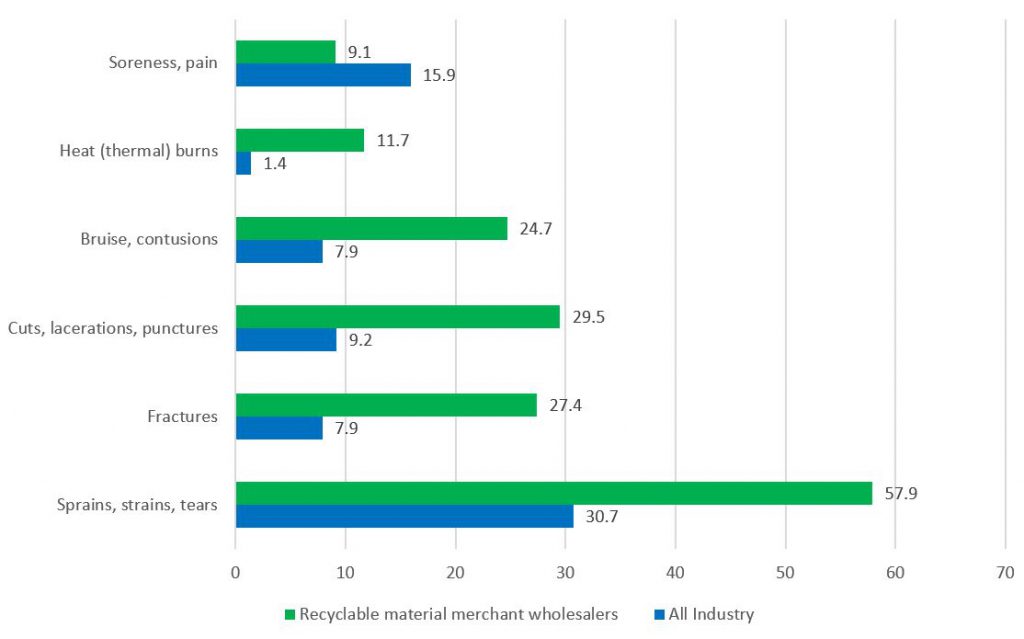

Overexertion injuries over time can manifest as either strains, sprains and tears or musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). MSDs in general are a serious concern among wholesale recycling workers and among the most commonly reported injuries. See Figure 3. In the recycling wholesale subsector, older workers aged 55 to 64 experience a disproportionate share of the burden of injuries. This older worker group represents 15% of the workforce and experiences 25.5% of the injuries and illnesses [BLS 2019b]. The aging wholesale sector population is particularly at risk for MSDs [ Anderson et al. 2020]. When older workers’ physical abilities do not meet job demands, they face increased injury risk [Fraade-Blanar et al. 2018, Baidwan et al. 2017].

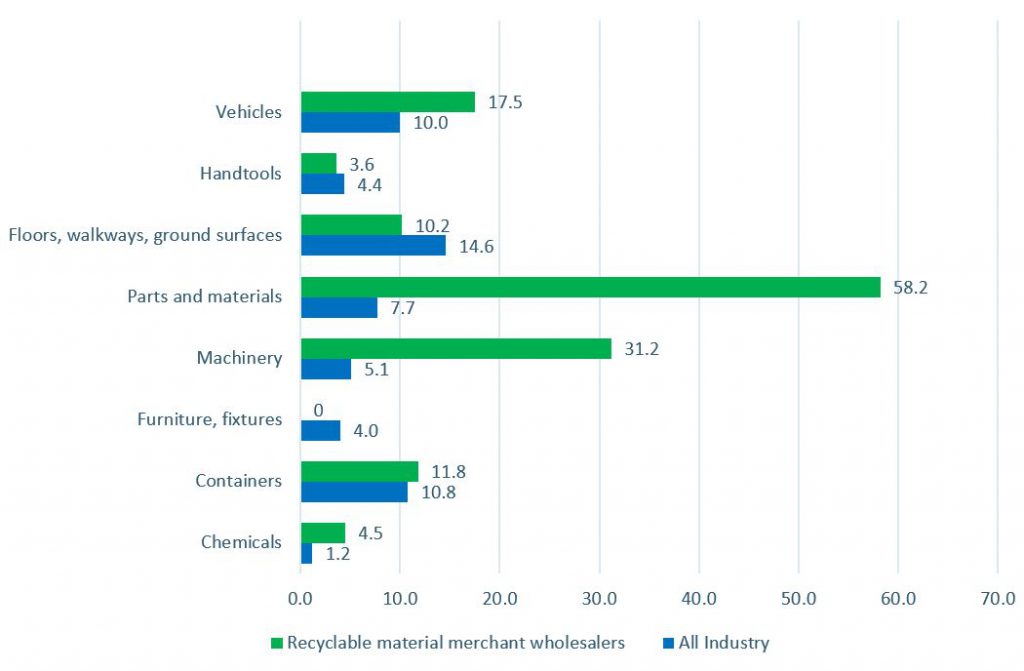

Sources causing the greatest disproportion of injuries in wholesale recycling compared to all industries include “parts and materials,” “machinery,” “vehicles,” and “chemicals.” See Figure 4.

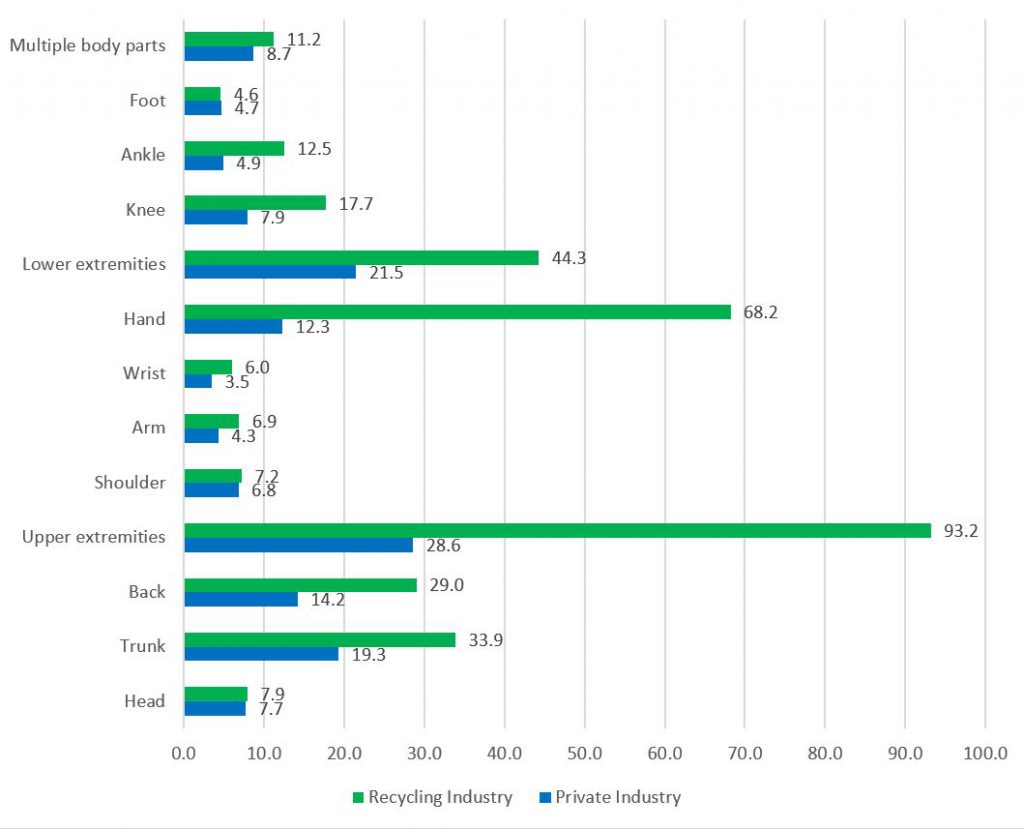

Body part injuries in wholesale recycling with the greatest disproportion of injuries compared to private industry include the upper extremities, , hand, and lower extremities [BLS 2019b].

How Employers Can Protect Recycling Workers

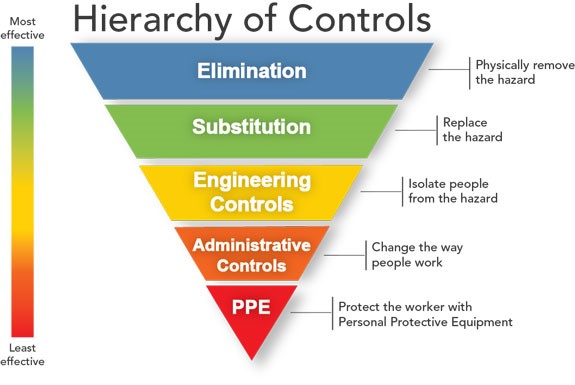

Use the NIOSH hierarchy of controls (Figure 6) to identify and implement strategies to keep workers safe and healthy. The most effective control is the elimination or substitution of dangerous materials and tasks. If the material or task cannot be eliminated or substituted, engineering controls should be implemented. Until such controls are in place, or if they are not possible, administrative measures and personal protective equipment may be used. Personal protective equipment is the least effective protection, as it puts the responsibility on the worker to use, maintain, and wear the equipment properly.

Engineering controls

Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA 2012] recommends the following engineering controls to reduce contact with objects and equipment; over exertion and bodily motions; fractures; and strains, sprains, and tears:

- Barriers placed between workers and overhead crane operations

- Powered or nonpowered devices to lift and reposition heavy objects, such as hoists or lifts

- Worker-controlled, motorized devices to move loads, such as powered dollies

- Systems that use mechanical means to transfer heavy or hot items from one location to another, such as powered trolleys or roller conveyors with shut-off controls

- Devices for raising or lowering the height of materials for easier handling, such as lift and tilt-tables

- Modified worktables and benches that can be easily raised or lowered to accommodate workers of different heights

- Enhanced tools with handles or materials that form a secure and comfortable grip and reduce awkward shoulder and wrist postures

- Mechanical impact tools supported on tool balancers to separate parts and materials

- Machine guards for shredders, all rotating and cutting devices, and where motorized pulleys are exposed

- Emergency stop cords along conveyors

Administrative controls and personal protective equipment

The majority of materials recycled include glass, paper, cardboard, metal, plastic, tires, textiles, batteries, automotive scrap, and electronic scrap [Siccode.com 2020]. Electronic scrap is a small, but potentially growing wholesale recycling industry.

Between 2013 and 2017, NIOSH performed four health hazard evaluations at a variety of electronic scrap recycling facilities to primarily identify toxicity and noise issues [NIOSH 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b]. These evaluations focused on preventing long-term health-related injuries and illnesses, such as those related to lead, cadmium, or noise that may not be as visible in the BLS data. Electronic scrap contains heavy metals and many chemical substances, including flame retardants. NIOSH investigators found flame retardants in the air, on employees’ hands and in the blood or urine. They also found lead and cadmium in some employees’ blood. Beyond chemical exposures, employees were exposed to hazardous levels of noise. Another common and extremely dangerous risk was not having machine guards on the shredding machines when in operation. In addition, some work activities involved heavy lifting, bending, and twisting, which could lead to back injuries. The following administrative and personal protective equipment controls were recommended in the NIOSH Health Hazard Evaluation reports:

- Start a medical monitoring program for employees exposed to lead.

- Follow the OSHA’s lead standard [29 CFR 1910.1025] (employees’ blood lead levels should remain below 10 micrograms per deciliter of blood).

- Evaluate the risk for musculoskeletal disorders and make changes to reduce risk.

- Use wet methods to clean (do not dry sweep).

- Provide employees with a lead-removing product to wash hands.

- Provide laundry facilities or contract a laundry service for employees exposed to lead or cadmium.

- Install a clean locker room area for employees to store personal items and food.

- Provide an employee eating area separate from work areas.

- Train employees on the proper wear and use of respirators and ear plugs, even if worn voluntarily.

- Require hearing protection in areas with noise levels at or above 85 decibels.

Industrial recycling provides a valuable service in protecting the planet. This protection should not come at the expense of workers who perform this work. Occupational injuries, illnesses, and deaths are wholly preventable. It is important to take measures to keep workers safe.

Jeanette Novakovich, MA, MS, PhD, is a Writer-Editor in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Vern Putz Anderson, PhD, CPE, is a guest researcher in the Division of Science Integration at NIOSH.

Adrienne Eastlake, MS, RS/REHS, MT(ASCP), is an Industrial Hygienist in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration and is a NIOSH Wholesale and Retail Trade Program Co-Coordinator.

Debbie Hornback, MS, is a Health Communication Specialist in the NIOSH Division of Science Integration and is a NIOSH Wholesale and Retail Trade Program Co-Coordinator.

References

Anderson (Putz) V, Schulte, PA, Novakovich J, Pfirman D, Bhattacharya, A. Wholesale and retail trade sector occupational fatal and nonfatal injuries and illnesses from 2006–2016: implications for intervention. Am J Ind Med. 2020:1–14 DOI: 10.1002/ajim.23063. https://www.mhi.org/downloads/industrygroups/ease/articles/ajim.23063.pdf

Baidwan NK, Gerberich SG, Kim H, et al. A longitudinal study of work-related injuries: comparisons of health and work-related consequences between injured and uninjured aging United States adults. Inj Epidem. 2018;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s40621-018-0166-7 .

BLS [2011–2018].Occupational Injuries/Illnesses and Fatal Injuries Profiles. Case and demographic incidence rates: Recyclable material merchant wholesalers, 2011–2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. https://data.bls.gov/PDQWeb/fw . Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

BLS [2020a]. Fatal injury rates. Hours-based fatal injury rates by industry, occupation, and selected demographic characteristics, 2011–2018. Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) – Current and Revised Data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm#rates Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

BLS [2020b]. TABLE R8. Incidence rates for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work per 10,000 full-time workers by industry and selected events or exposures leading to injury or illness, private industry, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/cd_r8_2018.htm Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

BLS [2020c]. Table 18. Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, 2018. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/cps/aa2018/cpsaat18.htm Accessed, February 21

BLS [2020d]. TABLE R5. Incidence rates for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work per 10,000 full-time workers by industry and selected natures of injury or illness, private industry, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/cd_r5_2018.htm#iif_cd_r5p.f.1 Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

BLS [2020e]. TABLE R7. Incidence rates for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work per 10,000 full-time workers by industry and selected sources of injury or illness, private industry, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/cd_r7_2018.htm Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

BLS [2020f]. TABLE R6. Incidence rates for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from work per 10,000 full-time workers by industry and selected parts of body affected by injury or illness, private industry, 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, BLS. Last modified December 17, 2019. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/cd_r6_2018.htm#iif_cd_r6p.f.1]Accessed Feb 4, 2020.

Coate P [2019]. Changing workforce demographics and workplace injury frequency. NCCI Research Report. National Council on Compensation Insurance; 2019.

Fraade-Blanar L, Sears JM, Chan KC, et al. Relating older workers’ injuries to the mismatch between physical ability and job demands. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(2):212–221. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000941.

NIOSH [2018a]. Evaluation of exposure to metals, flame retardants, and nanomaterials at an electronics recycling company. By Beaucham CC, Ceballos D, Page EH, Mueller C, Calafat AM, Sjodin A, Ospina M, La Guardia M, Glassford E. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Health Hazard Evaluation Report 2015-0050-3308, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2015-0050-3308.pdf.

NIOSH [2018b]. Evaluation of exposure to metals at an electronics recycling facility. By Grimes GR, Beaucham CC, Ramsey JG. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Health Hazard Evaluation Report 2016-0242-3315, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2016-0242-3315.pdf.

NIOSH [2019a]. Evaluation of exposure to metals and flame retardants at an electronics recycling company. By Grimes GR, Beaucham CC, Grant, MP, Ramsey JG. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Health Hazard Evaluation Report 2016-0257-3333, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2016-0257-3333.pdf.

NIOSH [2019b]. Evaluation of exposures to metals and flame retardants at an electronics recycling company. By Ramsey JG, Grimes GR, Beaucham CC. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Health Hazard Evaluation Report 2017-0013-3356, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2017-0013-3356.pdf.

OSHA [2012]. Solutions for the Prevention of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Foundries. OSHA 3465-08-2012. U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Department of Labor, Washington DC. https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3465.pdf

Siccode.com. NAICS Code 423930 – Recyclable Material Merchant Wholesalers, https://siccode.com/naics-code/423930/recyclable-material-merchant-wholesalers. Accessed Feb 8, 2020.

Posted on by