Workplace Accidents, Occupational Illness and the Long Road to Workers’ Compensation and Safety Policies around the World

Posted on byWorkers’ Memorial Day1 takes place annually around the world on April 28 as an international day of remembrance and action for workers killed, disabled, injured or made unwell by their work. This day also commemorates the enactment of the United States’ Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, put into effect on April 28, 1971. The Act sought to ensure safe and healthy working conditions for every working man and woman in the country. To this end, it established the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Not least, this Workers’ Memorial Day marks 135 years since the introduction of the first major law that attempted to address the distress caused by workplace injury, illness, and death — Germany’s accident insurance policy, which was introduced in 18842 following years of widespread debate. Workers, lawyers, scientists and politicians had battled for decades over whether workers or employers should be held responsible for “accidents” at work and whether accidents could be prevented in the first place. This law—and the debates which led to it—were by no means unique to Germany. The turn of the twentieth century saw a global boom in accident compensation and accident insurance policies,3 with over seventy countries and federal states enacting these laws between 1884 and 1918. Individual US states took part in this wave, for example, with Mississippi in 1902, Oregon and Montana in 1903, and Wisconsin and Ohio in 1911, alongside others.

These laws were all based on the same premise: accidents were part and parcel of work, and no one could be blamed for them. Following this thinking, workers would receive compensation if they were injured. If they died from an accidental injury, their families would receive a death benefit. Since employers were seen as gaining most from a workplace, it was up to them alone to pay for workers’ compensation.

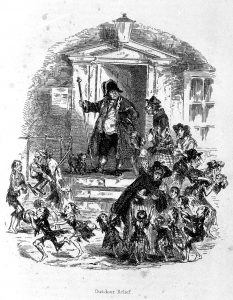

This system was revolutionary. It meant that workers too injured to return to work were no longer left to turn to charity and public funds for aid (Figure 1). It also meant that workers did not have to rely on trade unions, guilds and other labor associations for mutual aid in times of crisis following an accident. The adoption of workers’ compensation and accident insurance laws meant that workers would no longer have to face off against their employers at court, potentially damaging relations and resulting in job losses. Prior to the compensation laws, to claim compensation at court, workers had the difficult task of proving that their employers were responsible for the accident.

The timing of this global transformation was not simply a coincidence. The nineteenth century had seen industrialization take off across much of the world. New machinery meant that the pace of work grew faster, and that accidents became more frequent and more serious. The railway encapsulated this trend. It provoked a mixture of awe and fear because trains could deliver goods and people more quickly and reliably than before, but they forever changed physical landscapes and were behind some of the worst disasters of the nineteenth century. Incidents like the 1842 crash on the Versailles-Bellevue line outside Paris, France sparked global media attention and outcry about the dangers of the modern world. Although railway technology improved over time, these kinds of disasters continued to provoke horror and worry about the wellbeing of train passengers and employees alike.

The modern workplace, with its large factories, seemed especially dangerous when contrasted with earlier forms of predominantly rural work (Figure 3). Modern work seemed to require new forms of regulation, from health and safety policies like fencing in machinery to compensation laws for injured workers. Safety legislation often proved popular with workers, who wanted to prevent accidents from happening rather than deal with their consequences. Trade unions and lobby groups like the Socialist Second International regularly argued for these kinds of provisions. However, safety measures, from ventilation and hosing down surfaces with water to wearing goggles and protective garments, could prove expensive. These also meant intervening in how everyday life in the workplace was carried out. Employers instead favored compensation laws that tackled lost wages and medical expenses due to injury without interrupting how things were done in the workplace.

Occupational Risk

Meanwhile, over time, various investigators—from doctors to physicists, engineers and factory inspectors—began to notice common patterns related to accidents. Certain jobs were especially likely to involve certain kinds of accidents, and these accidents tended to involve particular groups of workers at particular days and times of the week. This meant that accidents could be charted and predicted with statistics, and paying for accidents could become predictable and done relatively easily through insurance.

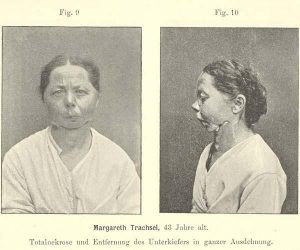

The concept of “occupational risk” gave rise to new accident insurance and compensation laws at the turn of the twentieth century; however, there was still disagreement about what an “accident” actually was. Was an accident something immediate and physical like a train crash? How would workers who suffered from occupational illnesses receive some form of assistance? Since the eighteenth century, various physicians like the Italian Bernardino Ramazzini had begun tracing connections between specific types of work and occupational disease. The science around occupational illness became more advanced in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. For example, the link between the manufacture of white phosphorus in the match industry and “phossy jaw” was widely known by the late nineteenth century and became the subject of an international ban in 1906 (Figure 4). Conditions that were invisible like black lung, which workers contracted through mining, were also understood increasingly well at this time, due in part to the introduction of new technologies like x-rays that could help with diagnosis.

Gradually, workers’ compensation and accident insurance was extended to some of these occupational illnesses as well. For example, in 1906, Great Britain began compensating conditions such as anthrax infections, which was a typical disease for those working with wool. By 1918, coverage was extended to include a wide range of ailments from nystagmus to miners’ silicosis. Over time, workers in industries or workplaces that did not seem especially dangerous were also seen as worthy of accident benefit. This meant that farm laborers as well as white-collar workers could now seek compensation for accidents. Many women who had been excluded from the earlier legislation that had targeted heavy industry were also now covered.

War and Workplace Safety

The coverage of a greater number of workers was further consolidated in the First World War, and later, the Second World War, when increasing numbers of men went out to battle (Figure 5). For instance, Italy extended accident insurance to its vast rural workforce in 1917.

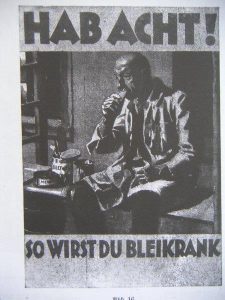

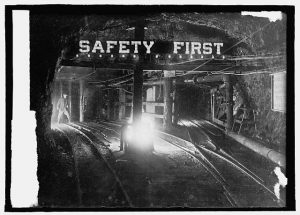

This era also saw a new imperative to maintain production in order to help with the war effort. It meant that there was little tolerance for workplace accidents, which slowed the manufacture of essential goods from food to TNT and airplanes. Starting just before the First World War, a new movement advocating workplace safety began to take hold. While scientists and engineers tracked what contributed to accidents, and how they could be avoided, companies began installing new safety guidelines as part of a broader “safety first” movement. This could be seen from the United States to Europe and was characterized by reminders at workplaces instructing workers to be careful and use safety equipment (Figures 6 and 7). During the war, this movement became more prominent, and it would continue into the twentieth century. Moreover, it filtered beyond the workplace, informing guidance on road safety and other areas, such as signage warning pedestrians to keep away from dangerous cliffs or slippery surfaces.

The wartime movement to keep up production had another important and long-lasting effect: a newfound emphasis on rehabilitation and the use of prosthetics for injured workers. This development was, in part, a carry-over from the treatment of injured soldiers. It could be found, for example, in new programs like Remploy in Great Britain, which was created in 1944 to retrain and deploy injured soldiers and workers.

On this Workers’ Memorial Day in 2019, we can think back on the evolution of workplace safety and the treatment of workplace injuries and illnesses over the last two centuries. Even the use of the term “accident” has evolved throughout this period. Around much of the world, workplace injuries, illnesses, and deaths are no longer viewed as an unavoidable cost of doing business. In the U.S., NIOSH and others have come to focus on prevention, and use the terms “injury” or “fatality” or state the cause of an injury (for example, a fall, collision, or burn), when referring to these preventable workplace incidents.

To be sure, this historical legacy has led to the increased protection of workers in most industries globally. Nonetheless, keeping workers safe also requires us to move beyond memorializing fallen workers as well as the achievements of the past. Countries around the world continue to face new challenges of industrialization, resulting in the rise of occupational illnesses despite widespread knowledge about their causes and prevention. As new chemicals and manufacturing processes are developed, it remains essential to monitor the safety and health of those involved.

Julia Moses is a Reader in Modern History at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. She is the author of The First Modern Risk: Workplace Accidents and the Origins of European Social States (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Notes

1. Also known as International Workers’ Memorial Day, International Commemoration Day (ICD) for Dead and Injured Workers, and National Day of Mourning.

2. It was adopted on 6 July 1884 and put into effect in October 1885.

3. Accident insurance is a form of social insurance with regular contributions into a fund that is used to compensate workers and pay for associated medical treatment. Workers’ compensation laws require employers to compensate workers for their injuries and medical expenses.

Posted on by