A Voice in the Wilderness: Alice Hamilton and the Illinois Survey

Posted on by

Today, on Workers Memorial Day we remember those who died from work-related causes and take stock of what we still need to accomplish to reduce the toll of workplace injury, disease, and death. As we do this, it may be helpful to look back at how far we have come and remember one woman in particular who helped to show us the way.

Not Just Counting Bodies

Before the beginning of the 19th century the state of the art for describing occupational health was primarily from the diagnosis of disease and death certificates; however, in 1909 our understanding of work and health began to shift from “counting bodies” to examining the social dimensions of work.

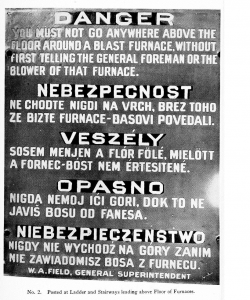

While a number of efforts to address dangerous workplaces were emerging, the Illinois legislature resolved to “thoroughly investigate causes and conditions relating to diseases of occupation, and to report to the governor the draft of any desirable bill or bills to meet the purposes announced in the resolution.” The Illinois Commission on Occupational Diseases, also known as the Deneen Commission” (Charles Deneen was Governor of Illinois), was charged in 1909 to determine the extent of occupational illness in Illinois. Ultimately, the Commission focused their work on industrial poisons and heat, as opposed to other physical, biological, or traumatic exposures, because the in-depth nature of the work needed to be well defined in order to be comprehensive. The Commission was charged with defining and finding poisonous occupations and gaining access to those workplaces; even though at the time there was no law or mandate for employers to allow outsider access. The outcome of the investigation had sentinel importance in Illinois, and marked the beginning of similar investigations by the federal government and other states.

Charles Henderson (1843-1915), a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago, was appointed as chairman of the Deneen Commission and was influential on its creation and membership. Although the first in the U.S., it was modeled after work done in Germany. Henderson had studied at the University of Leipzig and was involved in several social causes; including serving as presidents of the National Conference of Charities, the National Prison Association, and the International Prison Congress.

In Comes Alice

Because of her connection to Henderson through her work at Hull House (Hull-House was a settlement community founded by Jane Addams) and his knowledge of her avocation on the issue of worker health, Alice Hamilton (1869-1970) was invited to be one of five physicians, along with an employer, and two members of the State Labor Department, to make up the Commission. Until this time, Hamilton worked as a bacteriologist to earn a living, and as a volunteer primary care physician and resident of Hull-House in Chicago. Hamilton’s reflection on the state of the occupational health field in 1909 was that of “voices in the wilderness.”[1]

After first being named as a member of the Commission by Henderson, Hamilton was then selected to be the general supervisor of the investigation, “because we looked for an expert to guide and supervise the study, but none was to be found.”[1] So in 1910, Hamilton had the opportunity to lead the first survey of “industrial sickness” in the U.S: to investigate workplaces that used lead, arsenic, brass, carbon monoxide, the cyanides, and turpentine.[2]

The lessons from this experience resulted in an intensive “course” in the prevention of occupational diseases. Hamilton characterized her opportunity to work on the Deneen Commission as “…pioneering, exploration of an unknown field. No young doctor nowadays can hope for work as exciting and rewarding. Everything I discovered was new and most of it was really valuable. I knew nothing of manufacturing processes, but I learned them on the spot, and before long every detail of the …production was familiar to me.”[1] In addition, Hamilton reached out to “apothecaries, visiting nurses, undertakers, charity workers, and priests” who have important knowledge of workplaces and workers.[1]

The charge to the Commission from the Illinois General Assembly was:

Science, Policy and Communication for Occupational Safety and Health

Alice Hamilton’s formal education in medicine, bacteriology, and research methods, in combination with her informal education in settlement and community work converged to make her the ideal person for leading a study of poisonous trades in Illinois. On the one hand her knowledge and skills of these sciences strengthened her credibility with workers, industrialists and state bureaucrats, on the other, her background and experience in doing community outreach and organizing enhanced her comfort for finding and entering workplaces. Subsequently, she discovered that the field of industrial hygiene, the awareness, recognition, assessment, and control of workplace hazards, was the ideal discipline for addressing the “helplessness of the working class here in America.”[3]

As managing director of the investigation, Hamilton amassed a group of “twenty young assistants, doctors, medical students, and social workers” to assist in the investigations.[1] She visited almost every workplace in which lead was used. The Deneen Commission, learned of industries and occupations which used lead which had never before been identified and drew attention locally and nationally to the issues at both industry and government levels. The outcome was a recommendation in the Deneen Commission report, and subsequent recommendations for legislation for an Illinois Occupational Disease Law requiring employers who worked with lead, arsenic, and brass in manufacturing, or in lead or zinc smelting, to “provide safety measures and monthly medical examinations.”[2]

The Commission work resulted in the first comprehensive report in the U.S. on “the causes and conditions relating to diseases of occupations.” Hamilton became recognized as the expert not only in understanding and documenting occupational exposures, but also in communicating with workers, supervisors, and owners on ways to control exposures.[4], [5], [6], [7] Equally important as her groundbreaking research was Hamilton’s recognizing the need for widespread dissemination of the findings. Prior to the Deneen Commission report there was almost nothing published in the U.S. on occupational diseases or industrial hygiene.[1] Following the completion of the Deneen Commission Report in January 1911, Hamilton’s writings were extensive in the field of industrial hygiene; she wrote for popular, government, and scientific publications, reflecting the value she placed on publishing, information dissemination, and research to practice. Although Hamilton also wrote on many issues related to peace and social justice, her body of work in industrial hygiene and toxicology are her principal foci. Specific to industrial hygiene, Hamilton published numerous articles in popular magazines like The Survey, Harpers Magazine, and Atlantic (formerly The Survey), and over 20 bulletins for the USDOLBLS. In addition, she published over 20 articles in the Journal of Industrial Hygiene.

Do Hamilton’s Methods Apply Today?

| Alice Hamilton Awards |

| NIOSH honors Alice Hamilton’s work each year with an awards ceremony in her honor. The Alice Hamilton Awards recognize science excellence as the foundation upon which NIOSH generates new knowledge to assure safe and healthful work for all. The purpose of the Alice Hamilton Award for Occupational Safety and Health is to recognize the scientific excellence of technical and instructional publications by NIOSH scientists in the areas of Exposure and Risk Assessment, Epidemiology and Surveillance, Methods and Laboratory Science, Engineering and Control, and Education and Guidance. |

The Deneen Commission, under Hamilton’s leadership became a turning point in how we understand the relationship between work and health, as well as, the beginning of a new career. She continued to conduct and promote her effective investigative methods, which reflected her belief in disciplined inquiry, attention to detail, and documentation that provided irrefutably objective evidence until 1935 when she retired from Harvard University. However, she continued to write, publish and give interviews until the 1960s. Her life’s work was ultimately to change working conditions and practices in the workplace, impact state and national policies, and diffuse essential findings to the benefit of workers, industrialists, bureaucrats and students. The Deneen Commission, under Hamilton’s leadership, led the way to contemporary approaches to workplace health and safety. How well are we doing in the U.S. in fulfilling the charge of the Illinois legislature? Who are the contemporary “voices in the wilderness” in occupational health and safety? The Deneen Commission focused on workplaces with chemical and heat exposure, where would a similar commission focus its efforts in 2014? Hamilton’s approach was up close and personal when it came to investigating workplaces and communicating about workplace exposures; does her approach work today?

[1] Hamilton, A. (1943). Exploring the dangerous trades: The autobiography of Alice Hamilton, M.D. (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown.)

Posted on by