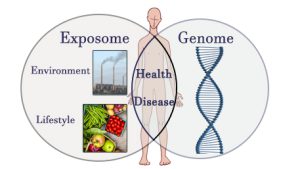

Interplay Between the Exposome and the Genome in Health and Disease

Posted on by A recent review assessed the interplay between environmental exposures and the human genome and showed ways that this interplay can alter disease risk.

A recent review assessed the interplay between environmental exposures and the human genome and showed ways that this interplay can alter disease risk.

Many diseases, such as birth defects and developmental disabilities, type 2 diabetes and cancer, are influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. The cumulative effects of environmental exposures prenatally and throughout life is referred to as the exposome. Studies of the exposome have identified associations between environmental exposures and disease, such as smoking and type 2 diabetes or alcohol consumption and systolic blood pressure. In addition to the exposome, the genome also plays a role in disease development and risk. For some diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, specific mutations in a single gene may be the main influence for disease development. For other diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, disease development may be influenced by small effects of many genes but still also greatly influenced by environmental exposures, such as physical activity or diet.

Neither the exposome or the genome contributes to disease risk or pathology in isolation. The interaction between these two fields provides more information on risk for disease development for individuals and populations. As a result, understanding the exposome, the genome, and the interplay between them is an important step for understanding disease development and improving disease prevention.

Gene-environment Interactions

One way the exposome and genome interact is through gene-environment interactions. Gene-environment interactions refer to when the impact of an environmental exposure differs between individuals with different genotypes. For example, specific genetic variants modify the risk of developing Parkinson disease after exposure to organophosphate pesticides. Another scenario example is when in which individuals with the same genotype, but different levels of environmental exposure, could have differential health impact. For example, studies have looked at either active and at passive cigarette smoking exposure among individuals homozygous for delta F508 and found different impacts related to the level of the environmental exposure.

Along with providing insights into the biological mechanisms for diseases, gene-environment interactions also provide information for which populations may be at a higher risk for disease after certain environmental exposures.

Epigenetics

Another way the exposome interacts with the genome is through epigenetics, the process of altering gene expression without changing the DNA Sequence. Epigenetics is a dynamic process that can be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, such as smoking and air pollution. While epigenetic dysregulation is an important contributor to certain diseases, such as Angelman syndrome and certain cancers, more investigation is needed to better understand how environmental-based changes in epigenetics influence disease risk. Currently, epigenetic markers can be used as biomarkers for environmental exposures, such as smoking and air pollution. Epigenetics has also been used as a marker for biological aging allowing for the study of how exposures may accelerate or decelerate biological aging.

Public Health Implications

A better understanding of the interaction between the exposome and genomics is important for quantifying disease risks and outcomes as well as identifying populations of higher risk for worse outcomes due to environmental exposures. More broadly, adding genomics to public health investigations of environmental risk factors could strengthen the causal interpretation of associations between exposures and health outcomes and lead to preventive interventions focused on modifiable risk factors.

Posted on by