Peeling the Pyramid, Scaling the Onion—How to Implement Genomic Medicine

Posted on by In spite of the promise of genomics and related technologies for a new era of precision healthcare and disease prevention, only a handful of genomic tests and applications have been recommended for use in clinical practice. Nevertheless, implementation of even the few recommended genomic tests is lagging. For example, implementing the 2005 USPSTF recommendation on genetic counseling of high risk women for BRCA testing is still not optimal, in spite of years of efforts by health care providers and genetic counselors. A recent study from a national sample of 14.4 million commercially insured patients shows underutilization of BRCA testing to guide breast cancer prevention among African-American and Hispanic women compared to whites. In addition a recent survey of primary care providers showed that only 19% consistently recognize the family history patterns identified by the USPSTF as appropriate indications for BRCA referral for evaluation. Likewise, implementing the 2009 EGAPP recommendation on testing all new cases of colorectal cancer for Lynch syndrome to reduce morbidity and mortality in relatives is just getting started. Substantial challenges in the healthcare system currently exist in the identification of Lynch syndrome in patients and their affected relatives. A Lynch Syndrome Screening Network was recently launched to accelerate research and implementation of Lynch Syndrome testing.

In spite of the promise of genomics and related technologies for a new era of precision healthcare and disease prevention, only a handful of genomic tests and applications have been recommended for use in clinical practice. Nevertheless, implementation of even the few recommended genomic tests is lagging. For example, implementing the 2005 USPSTF recommendation on genetic counseling of high risk women for BRCA testing is still not optimal, in spite of years of efforts by health care providers and genetic counselors. A recent study from a national sample of 14.4 million commercially insured patients shows underutilization of BRCA testing to guide breast cancer prevention among African-American and Hispanic women compared to whites. In addition a recent survey of primary care providers showed that only 19% consistently recognize the family history patterns identified by the USPSTF as appropriate indications for BRCA referral for evaluation. Likewise, implementing the 2009 EGAPP recommendation on testing all new cases of colorectal cancer for Lynch syndrome to reduce morbidity and mortality in relatives is just getting started. Substantial challenges in the healthcare system currently exist in the identification of Lynch syndrome in patients and their affected relatives. A Lynch Syndrome Screening Network was recently launched to accelerate research and implementation of Lynch Syndrome testing.

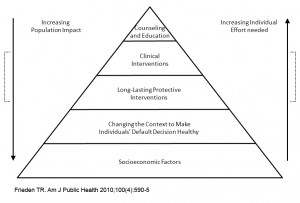

So what would it take to successfully implement recommended genomic medicine applications? A mixture of multilevel interventions and research to support them are needed for successful implementation and evaluation. In 2010, Dr. Thomas Frieden, CDC Director introduced the impact “pyramid” as a way to gauge the interventions based on population health impact (see figure 1). In the context of genomics and other health fields, a 5-tier pyramid can describe the impact of different types of clinical and public health interventions and provides a framework to improve health. At the base of this pyramid-interventions with the greatest potential impact- are efforts to address socioeconomic determinants of health. In ascending order are interventions that change the context to make individuals’ default decisions healthy (such as policy and coverage), clinical interventions that confer long-term protection (e.g. newborn screening), ongoing direct clinical care, and health education and counseling of patients and populations. Interventions focusing on lower levels of the pyramid tend to be more effective because they reach broader segments of society. Implementing interventions at each of the levels can achieve the maximum possible sustained public health benefit. Obviously for successful implementation of genomic medicine we need to combine interventions at multiple levels that include among others things policy change, education and integrated clinical programs as well as surveillance to measure impact.

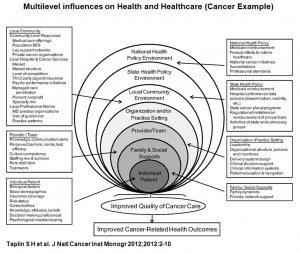

Nevertheless, extensive analysis based on 13 papers published in a recent JNCI monograph indicate that we know very little on how to combine interventions at multiple levels in the context of cancer in general, and genomics in particular, to successfully implement genomic applications in practice, and to achieve the best possible outcomes at the population level. As Taplin et al state in the introduction to the monograph, “health care in the United States is notoriously expensive while often failing to deliver the care recommended in published guidelines. In this monograph, we emphasize that health-care delivery occurs in a multilevel system that includes organizations, teams, and individuals. The notion that multiple levels of contextual influence affect behaviors through interdependent interactions is a well-established ecological view.” The monograph adopts an “onion” conceptualization (see figure 2) that uses levels of human aggregation to identify a hierarchy of potential intervention targets. The targets are the individual, including biological factors, beliefs and attitudes, sociodemographic characteristics, and risk factors; the provider/team, including skills and attitudes of providers, and the functioning of the provider team; family and social supports, including social networks; the organization or practice setting, including human and capital resources and processes designed to improve care; the local community environment, including local health-care markets, and social and professional norms; the state and national environments, including state policies, programs and other factors. The “onion” model identifies potential levels of intervention, it does not specify the mechanism of effect of the levels on each other or the behavior of providers and people seeking care. So getting it done right for genomic medicine, as in other areas of health care, requires the combination of research and practice at multiple levels. Whether we use the image of the “onion” or the “pyramid” to help us in our conceptualization of what needs to be done, it is clear that many actors have to come together to assess how best to implement genomic medicine through a robust research agenda while at the same time developing scalable implementation programs There is a need for implementation research approaches to scaling up and sustaining effective interventions based on core scientific principles and social equity values. Through its convening and communication functions, and targeted pilot funding, CDC will continue to work with many partners and stakeholders to accelerate the implementation of validated genomic applications for the benefit of population health.

Posted on by